'An aphorism, properly stamped and molded, has not been "deciphered" when it has simply been read; rather one has then to begin its interpretation, for which is required an art of interpretation.' -- Nietzsche, 'On the Genealogy of Morals'

|

|

'An aphorism, properly stamped and molded, has not been "deciphered" when it has simply been read; rather one has then to begin its interpretation, for which is required an art of interpretation.' -- Nietzsche, 'On the Genealogy of Morals'

|

|

|

Levinas, the face, ethics

« Previous |

|Next »

|

|

|

May 12, 2006

Levinas' various phenomenological arguments give confidence that we are not doomed to a Hobbesian state of nature. However, the question of the nature of ethics, the "source" of the break with being, is a difficult one. For Levinas, it is the face of the other that establishes this order, a dis-ordering of myself and a re-orientation towards the other.This requires that we understand Levinas' use of the term "face."

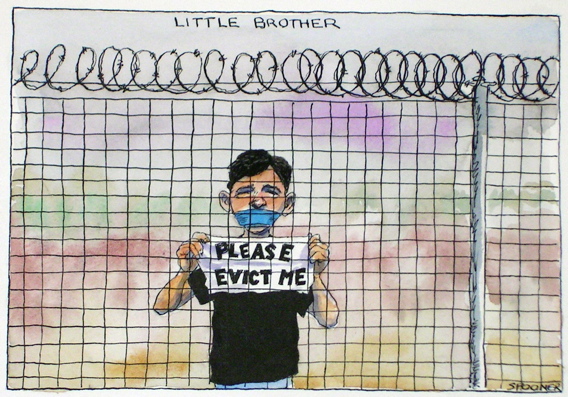

John Spooner

In Totality and Infinity Levinas says :

The way in which the other presents himself, exceeding the idea of the other in me, we here name face. This mode does not consist in figuring as a theme under my gaze, in spreading itself forth as a set of qualities forming an image. The face of the Other at each moment destroys and overflows the plastic image it leaves me..(pp.50-51).

Normallly we encounter a face in a context--that of a friend, a student, a teacher or a lover. We remember a face more easily than a name. Why so? Perhaps the visual is stronger than the verbal. Or maybe it is because faces are the location for the expressions and emotions which indicate character and subjectivity?

Levinas' understanding of the face of ethics is more radical than this, as it involves a signifyingness of its own independent of this meaning received from the world. In Ethics and Infinity, conversations with Philippe Nemo, Levians says:

There is first the very uprightness of the face, its upright exposure, without defense. The skin of the face is that which stays most naked, most destitute. It is the most naked, though with a decent nudity.... The face is meaning all by itself...it leads you beyond. (trs. by Richard A. Cohen, Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1985, pp. 86-87).

The face of the other, whether masked by make-up, earrings, artificial coloring, scarves, and so forth encounters me directly and profoundly. Face to face encounter with the other discloses the other’s weakness and mortality. Naked and destitute, the face commands: “Do not leave me in solitude.” We ought welcome, be hospitable to, the Other who encounters us, asthe stranger who comes to me in my mundane, self-centered existence demanding from me a “Here I am.” Levinas is clear that what is given in the face-to-face encounter is the fact of another's independent expression.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

One wonders whether Levinas' choice of the figure of "the face" to make his basic point about a surplus or excess of meaning embodied in experience beneath the level of any (order of) propositional/semantic meaning, which is traced to the relation to the other, is (motivated by) a response to the Sartrean account of the "gaze" of the other, to which it is virtually an inverse account.

For Sartre the gaze of the other evokes the desire to "capture" the freedom of the other. Levinas' account of freedom is the exact opposite to that. His basic point is that freedom has always been implicitly conceived of and "measured" by its relation to causality in Western metaphysics, resulting in its interpretation, as "autonomy", as a self-mastering mastery. (There is a similarity to the Horkheimer/Adorno account in the "Dialectic of Enlightenment" here, though the subject-object conceptual means of the latter renders their account thoroughly entrapped in aporia.) By conceiving of freedom, rather, in terms of the modal relation to the other, Levinas embeds it all the more in the reality/materiality of the world, even as it uproots the self from its continuity with itself and its (defensive?) control over possibility.

This leads to the difficult problematic of an "heteronomous" freedom, wherein responsibility "precedes" freedom, seemingly violating the traditional notion that moral responsibility presupposes freedom, as if it were a matter of a deterministic account, which embargoes the role of choice in constituting a self.

But, of course, Levinas' point refers to the ethical conversion and transformations of the self, which does not eliminate choice, but rather lends it its weight. That leads on to a still broader criticism of the way "activity" has hierarchically dominated Western metaphysical thinking, (the paradigm case being the Aristotelian godhead, which, as "nous noesikos", is characterized as pure actuality/activity).

Hence a revaluation of the role of passivity, more basic than the passivity involved in the agent/patient relation, is undertaken: the "passivity" of woundedness and trauma, whereby the splitting of the self is also its openness to the other (without requiring an empathic/projective derivation of the relation), rendering a concrete account of the linkage of the normativity of justice to compassion and solidarity and an account of ethical action as reparative/transformative in a way that is neither historicist, nor "eternal" or timeless.

It seems to me that Levinas is following up on Heidegger's critique of the metaphysics of the will, in a way, characteristic for him, that is at once quite close to and distant from Heidegger. But the challenging originality of Levinas conception of the other, as something unobjectifiable, hence irreducible to concept or category, is that it is neither being, nor nothingness, (which would seem to be the only alternatives that ontology would allow), neither "positive", nor "negative", but rather ineliminably "otherwise" than being, in a way that can not be thought, but provokes and motivates thinking.

Hence the other can only be delineated from the traces it leaves in experience, in the way that it affects rather than effects the self. That placelessness of the other is its "utopian" character, resulting in a conception of ethics as a kind of practical, non-idealistic utopianism without any point of "final" arrival, from which resistance to the violence (and paranoia) of the socio-historical world receives its mandate.