February 29, 2004

Outside Looking In

Gary, glad to read that you are on the ball, although I guess that turning that word into red for me spoke for itself. I agree with you that reading most modern philosophy books is a waste of time. I can handle Adorno, Bataille, Benjamin, those sort of guys but most other stuff leaves me cold, even the secondary texts on these guys. When I read Adorno, for instance, this is particularly true of him, I discover that my previous readings were shallow, partly blind, or only half readings. This means that I get more from his writings – the same writings – each time I go to them. They seem to get better and better.

Hey, shit! I’m sorry if I sounded like I was hassling you. I know you’re busy with the pollies and their pollywaffle. It’s a job and it sounds like a shithouse one at that but everyone needs bread. ‘Give us this day our daily dread and forgive us our trespasses.’ While the contemporary philosophers are irrelevant, the pollies are positively pernicious. There’s an aphorism by Canetti that describes both groups well:

‘The last of the month, I climb down into my ruins, a ridiculous lamp in my right hand, and I tell myself the deeper I go: it’s no use. What faith can lead to the core of the earth? Whatever you, whatever another, whatever each of us does – it’s no use. Oh, vanity of all strivings, the victims keep falling, by the thousands, the millions; this life, whose holiness you want to feign, is scared to no one and nothing. No secret power wishes to maintain it. Perhaps no secret power wishes to destroy it, but it does destroy itself. How should a life that is constructed like a bowel have any value?’

Canetti continues, describing the peaceful comfortable day of the average academic philosopher:

‘The peaceful day some people experience is hypocritical. The torn-up things are more true. The peaceful ones envelop earth with the leaves and slowness of plants, but these nets are weak, and even if they are victorious, the fleshy destruction continues under their green covers. The powerful man swaggers about with his biggest stomach, and the vain man is iridescent in all the colours of his innards. Art plays a dance for the digesting and suffocating. It gets better and better, and its legacy is guarded as the most precious good. Some people delude themselves with the idea that things could come to an end, and they calculate catastrophes on top of catastrophes. But the deeper intention of this torment is an eternal one. The earth remains young, its life multiplies, and new, more complicated, more distinct, or more complete forms of wretchedness are devised. One man pleads with another: Help me, make it worse!’ (The Human Province, p. 107)

I’m hanging out with the guys and gals with iridescent guts; you’re hanging around with the ones with the very biggest bellies – and sagging tits too (I think that’s how one of your chiefesses described them in a different context some time ago). Canetti and Adorno are at one on this: those who have truly resigned are the ones who proclaim a way forward when none can be found. The phillies and the pollies have both resigned. They just get terrific superannuation and a three-ring circus to play in.

In the meantime, what do we do? Answer: we write. This isn’t a proposal; it’s a description. We Write. But who do we write for if not for the fat guts and the colourful gizzards? According to Karen Blixen, God is whoever it is you write for when you don’t write for them. And I’m writing this on a Sunday! It must be an act of devotion! I’m writing to the same guy Bukowski was writing to when he wrote his poems that weren’t really for people to read. Sure, you can read them, but it’s like reading other people’s mail.

Klossowski gives me the words to say what I want to on this question – hang on, I’ll just look up when it was that I talked about Klossowski… here it is… it was… ‘Klossowski On Art’ (January 15) [In red please, Gary]. Just as an aside that is doubly virtuous because it allows me to say something else about Balthus, the name ‘Klossowski’ is pronounced ‘Kuas’ and not ‘Klo’. According to Balthus, it’s a very old Slavic name meaning ‘corn cob’. It also exists in Russian. His father hated being called ‘Klo’ (Balthus In His Own Words, pp. 17-8). Anyway, the idea I get from old Pierre Corn Cob is the distinction between expression and communication. The first is to do with phantasms, the second to what is imposed from outside. In art the two become mingled because expression is always couched in stereotypes – symbolic modes of communication. Modernism, as distinct from other periods in art is the time when the phantasm pretty much gives up on expression in order to attack the stereotypes.

Canetti gave up but he didn’t stop writing, and what he wrote broke new ground in terms of literary form. I’ve called the material I quoted an aphorism but the term doesn’t fit completely comfortably. Adorno possibly captures this new form best in describing the material in Benjamin’s One-Way Street. He wrote of Benjamin’s work that, rigorously conceived, it ‘excludes not just fundamental themes but all analytical techniques of composition, development, the whole mechanism of presupposition, assertion, and proof, of theses and conclusions. Just as the uncompromising representatives of the New Music tolerate no “development”, no distinction between theme and elaboration, and instead require that every musical idea, indeed its every note, stands equally near to the centre, so too is Benjamin’s philosophy “athematic”. It too is dialectic at a standstill to the extent that it admits of no period of development but rather gains its form from the constellation of its particular enunciation. Hence its affinity to aphorism’ (On Walter Benjamin G. Smith (ed) p. 14). I’m inclined to look on books like Bataille’s On Nietzsche in this way, as well as the volumes of ‘jottings’ by Canetti.

To mine, this is what lies behind the disagreements I always have in reading groups and seminars. Academia, even now in its corporatist and post-modernist form, relies on fundamental themes, analytical techniques of composition, development, on presuppositions, assertions, and proofs, on theses and conclusions. That’s why Benjamin was never allowed into a university. That’s why we’re outside. I live off a woman with some crumbs from academia on the side; you mix the female source with some funds for working with pollies. We’re birds of a feather. Mostly we’re locked outside the cage. But then, being locked out is a bit like being locked in, isn’t it?

February 28, 2004

So little time

Trevor,

I do read your work, even if my comments on your posts are few and far between. The reason for this is at the moment I'm working fulltime and that means long hours. This will last until the end of March. I've little energy after a 10-12 hour day---the Canberra pole involves up to 14 hours a day living amidst chaos.

This high intensity political life is sometimes called organized or creative chaos, but I often experience it as hopeless chaos. It is working on issues in a burrow whilst listening to parliamentary debates & media commentary on the television, fielding calls from the media, whilst responding to things unravelling around you. It's living chaos, where time or life is marked by images from TV and reality is defined by what the news said reality had been an hour ago. It's a world where you drown in information, whose historical span is a few days.

You step outside Canberra on Thursday evening, catch the commuter plane back home, only to discover that all that happened in Canberra made little impact in Adelaide. What in the hell was the point of all that, you ask yourself?

You can see the reasons for my current attraction to a philosophy of becoming, intensity and event.

I have no idea about the Hegel quote. Hegel was a patriarch for sure, with all the stuff he wrote about the family in the Philosophy of Right. The standard stuff about women being inferior to men and keeping to their place in the family. Typical 19th century bourgeois fare.

On the other hand, desire is the dynamic that drives Hegel's master servant dialectic.

I haven't read Derrida's old text Spurs so I cannot really comment on the Hegel quote. From the bits that I know of it, the text engaged with a certain essentializing of "woman" in the US seventies feminism. This deconstruction called critical attention to some of feminism's assumptions whilst contesting the phallocentrism of Nietzsche, Freud etc. The context is to object to more conventional/traditional representations of femininity.

What sits behind this is Heidegger's metaphysical reading of Nietzsche which Derrida contests. That is rarely discussed.

I've so little time to read this sort of material these days. It is hard for me to shrug of the feeling that reading modern philosophy books is mostly a waste of time. I've taken the pathway of the primacy of the practical over the theoretical that is expressed in for instance, in Gadamer's rehabilitation of the Aristotelian notion of phronesis that is based on praxis and ethos.

February 27, 2004

Reading Groups

I went to my Star Of Redemption reading group last night. There were seven of us there and it looks like it might be settling down to about that number, three old girls, three old guys, and a youth – possibly two youths. What a setting! relics studying relics.

I’ve discovered what I do that always leads to disputation in any such groups I join. I listen to what is going on, a story about the ideas of some hundred-year-old German, usually a Jew. After a while I notice that the discussion takes a form that gets up my nose. I sense an underlying philosophical difference. I know. You’re thinking: strange thing to get into a dispute over. Well, I’m a strange guy, I guess. I’ve got my views. I’m sick of eating somebody else’s shit. So I deal with the German, whoever he is, by having a look at what Benjamin or Adorno have to say on the matter. Often they articulate something I’m already thinking. Anyway, I take this stuff back to the group with me. Therein lies the bone of contention.

Last night I caused an immediate irritation by saying that Protestantism was a bourgeois religion – I can’t remember the context. Anyway, it doesn’t matter. The point is, this caused immediate concern, not from the old girls who mostly see themselves as less informed than the old guys, the latter of course happen to be academics, one defrocked, twit, moi. (I don’t speak French, by the way, so don’t anyone try to converse with me in that language.) I digress. The other old guys didn’t know, the bourgeoisie weren’t in charge when… the nineteenth century is really the bourgeois century… you can guess the sort of stuff, concerns over the specificity of particular circumstances, as if anyone said anything about direct class rule or the grand class direction of history. They hummed and harred. They’d smelt a commie under all the words and they didn’t like it.

I said some irrelevant things about the bourgeoisie being the middle class and so on – you can guess the stuff. I don’t need to tell you. The thing is, there’s a new worldview that shows up around the Renaissance and it is related to the activities of an emerging class on the world stage – for this last extravagant term read ‘Europe’. Whether or not they didn’t really run the show in Germany until the 1900s doesn’t really matter. It’s beside the point.

I don’t know whether it my paranoia or not but, in these conversations, I always get the feeling from my combatants that if you use the word ‘bourgeoisie’ you are somehow giving it a pejorative twist, which puts them on the defensive. For a so-called ‘Marxist’ it may be a term of abuse. The Nazis used the word in rather this context. It’s not my view. In the sense that I am using the term we are all bourgeois in this sense although we live in a post-bourgeois era. Corporate administration doesn’t really like too much bourgeois affectation. It prefers some amorphous mass, a déclassé society. Just like in the extermination camps, everybody comes from the same declass (if you’ll forgive the neologism).

Déclassé society is the outcome of bourgeois machinations. Marxists would say that it was a result of the evolution of capital. I like that way of saying it too, so I must be a commie. Jesus Christ! I’m getting off the track again. It point is, as Hannah Arendt argued in Volume Two of The Origins Of Totaliterianism, imperialism is the political consciousness of the bourgeoisie. If you’d like some of those concrete facts, albeit a bit removed, in Britain it came about when the cabinet was drawn from the House of commons instead of the House of Lords. I think the Duke of Wellington – the soldier, not the pub – was the last prime minister from the H of L but I could be wrong. The corporation soon provided the administrative model and they were away. They haven’t looked back. If they did they’d notice the pile of rubble. I won’t go on. You’ve heard enough. You’ve made your decision: commie ratbag. Q.E.D. (whatever that means).

You may even be getting a bit shirty by now. When’s he going to get on with the philosophical conversation? you might be wandering. What’s all this got to do with Bataille and inner experience? Well, the answer is, not much, at least not directly. Although… sometimes when I’m sitting there with a bunch of old ducks and drakes upsetting everyone by being an opinionated commie ratbag, I something think, wouldn’t be better if we just had an orgy? But I never say anything. I just go on with the argument.

February 25, 2004

A Dog's Life

I know. I’ve been slack about writing for our web page, or blog or whatever it’s called. I guess everybody’s getting the drop on me this week. It’s not that I’m in a deep depression or anything like that. It’s just that – well, you know how it is. I have joined a Star Of Redemption reading group. The next meeting will be the fourth. The Star is so far from what we’re talking about that it is hard keeping both trains of thought going. I’m not ambidextrous. On top of that, I am writing a paper on Adorno for the conference. (See the entry for January 19. Perhaps Gary will put the words in red for me – make a link or whatever you call it. We’ve been meaning to get this up under the conference heading but so far there’s just some gobbly-goog there – at least, that’s what shows up on my computer.) I’ll tell you about this paper in due course. Is it all right to subvert the conversation to Adorno? Only, as I said, I’m not ambidextrous. Right! To work:

No, I didn’t know that Bellmer did the illustrations for the second edition of Story Of The Eye. I’d love to see a copy. I guess it would cost a fortune to buy, if you could find one. All that I know about Bellmer I’ve got from the Web. Gary, you seem to be ahead of me in this regard. Why don’t you write us a short biography? That would be great.

From what you’ve put up so far, if Bellmer is a visual Bataille then his work looks very surrealist. I think most people have a funny idea of what surrealism is. They see it as an historical event which was killed off by the Second World War – the Soviet guys called it the Great Patriotic War. That’s bullshit too. Let’s not beat around the bush. As a matter of historical fact, it was the Second Great Imperialist War. Indeed it represented imperialism at its most mature: it was the first Great Corporatist War. Anyone who thinks that a load of crap like that could kill off surrealism needs their head read.

Surrealism is an intellectual position. Benjamin called it ‘the last snapshot of the bourgeoisie’. The remark is ambiguous. Is it the last snapshot taken of the bourgeoisie or the last snapshot taken by the bourgeoisie? It’s both – that’s what I think. Surrealism needs to be seen in the context of a general attitude at the beginning of the twentieth century. The Star Of Redemption is a good example of this attitude. Franz Rosenzweig wrote the book in the context of a number of factors, including the first great imperialist war but also the assimilation of German Jewry during the nineteenth century, which Rosenzweig saw as a domination by enlightened rationalist thinking. Indeed, because it was the highest expression of systematic thinking in philosophy, Hegelian philosophy is Rosenzweig’s target. The drive behind surrealism is not dissimilar to Rosenzweig’s move – both are a reaction against the domination of systematic reason. Here is where the similarity ends, however. Rosenzweig takes the high road and opts for existentialism. The surrealists take the low road and opt for … what? Rosenzweig wanted to be like God. The surrealists wanted to be like Dog. Is there another path? Who knows? There are animal tracks shooting off in all directions. When you’re out in the bush they’re always worth following.

Here’s a question for you, Gary? This will test whether you’re reading my stuff or not. Anybody who is should look out for Gary’s reply. Anyway, back to the question. I got an email from Luke. He said that he and Wendy were having a dispute. Apparently, in his book Spurs Derrida says that Hegel wrote an ‘analysis of the passivity of clitoral pleasure’. Wendy’s position is that Hegel wrote no such thing. I don’t know my Hegel well enough. What do you think?

If he means by the passivity of clitoral pleasure that the ladies just lie there then I don’t think that is right. I believe that some ladies like to jump around a lot. If they didn’t in Hegel’s day then that probably means that the ladies in his particular social group were probably pretty repressed and mightn’t have got much pleasure out of sexual relations. They might have thought that the right thing to do was to lie still and breath gently but regularly. Something like Molly Bloom’s soliloquy might have been what went on in their heads while all this took place. And after all, the pleasure ultimately comes from rubbing sensitive skin. After a while it’s a bit difficult to get too excited about it. The rest depends on the social – but hey! we’re back to Bataille. Perhaps all this stuff does go together after all.

I said I’d say more about Balthus so here’s an anecdote. When quite young he once had dinner with Matisse and Bonnard, among others. Bonnard was a jovial laughing sort of man apparently. Well, anyway, at one point Matisse said to Bonnard, ‘Bonnard, do you realise that you and I are the greatest painters of our age,’ and with that Bonnard’s face dropped until he took on the look of deepest melancholy, and he replied, after thinking for a moment, ‘If you and I are the greatest painters of our age, Matisse, then I weep with sadness.’

February 24, 2004

Bukowski: Poems#12

question and answer

he sat naked and drunk in a room of summer

night, running the blade of the knife

under his fingernails, smiling, thinking

of all the letters he had received

telling him that

the way he lived and wrote about

that –

it had kept them going when

all seemed

truly

hopeless.

putting the blade on the table, he

flicked it with a finger

and it whirled

in a flashing circle

under the light.

who the hell is going to save

me? he

thought.

as the knife stopped spinning

the answer came:

you're going to have to

save yourself.

still smiling,

a: he lit a

cigarette

b: he poured

another

drink

c: gave the blade

another

spin.

Charles Bukowski

February 23, 2004

Bellmer's drawings

Some relief from philosophy:

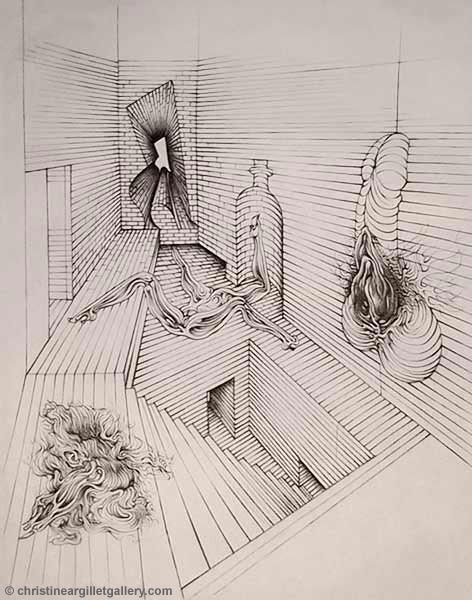

Hans Bellmer, The Brick Cell, date unknown

Does the image refer to the Marquis De Sade? (More on de Sade here.)Or is about forbidden sexual longing in the unconscious?

More Hans Bellmer prints here

February 22, 2004

Bellmer & Bataille

Trevor,

Have you come across any of Hans Bellmer's drawings for Bataille's Story of the Eye in your wanderings? Apparently Bellmer did the illustrations for the second edition.

This is the most extensive online resource on Bellmer that I could find. We have some photographs and these from the 1950s and 1960s; these of no date; these drawings on de Sade that seem to have been done in the 1960s.

But nothing in relation to Bataille.

Bataille: On Nietzsche#15

'Morality is simply weariness'.

That quote from Nietzsche opens chapter 6 of part 2 of On Nietzsche.

Even though sexual desire opens a space of sensual excess beyond the world or morality subordinated to utility, there is a shamefulness attached to a man's desire for a woman. So says Bataille. In the process of affirming life Bataille works with a sinister-sinful-loathing structure to how Bataille sees the moral law of sexuality.

(Bataille does not mention women's desires for men. Its all about men desiring women. Do women lack this element of shame? Are women then consequently seen, and feared by men, as shameless? This is the 1940s's remember when the German fascists were in control of France.)

If desire threatens the self's dissolution, then the shame is being seen as disgusting, vile and a sicko. Shame is not the sexual longing to break down the limits--ie., the savage eruption of exuberance. It the desire for evil.

Bataille says that morality leads to exhaustion as it is a barrier to the summit that is the moment of risk taking.

next previous start

February 21, 2004

Surrealism & sexuality#5

It's odd isn't it. In 1941 Surrealism was declared dead and has been described as such in all the conventional art history books since that time. Abstract modernism became identified with modernism in the art institution.

Surrealism was seen as one of the most vilified and degraded forms of cultural and artistic expression. It was banished.

An example?

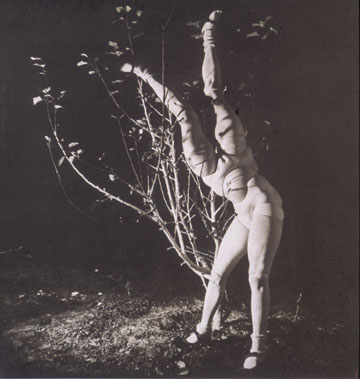

Hans Bellmer, The Doll(1935)

So the work of Hans Bellmer, with his manipulated female dolls, bondage tricks and photos of women fingering themselves as they stood, hitching their skirts up, over open toilet bowls, has been regarded as beyond the pale.

And now? We can interpret Bellmer's the work from Bataille's perspective: in a nihilist world we different kind of socio-sexual disturbance and confusion about bodies, power, sexuality, fragmentation and otherness.

February 20, 2004

Surrealism as a way of knowing

I came across this passage on surrealism over at the wonderful Artrift site. It's a quote from Wallace Fowlie, Age of Surrealism, [Bloomington, Indiana Univ. Press, 1963], pp. 202-203.

"Wisely surrealism was never defined by the surrealists themselves as a new artistic school. Rather it was defined as a way of knowledge. Breton has persistently condemned a pragmatic view of life which would emphasize a calculated search for the kind of happiness that could only be limited and prudent. In proposing to man the hope for existence, surrealism advocated as means for achieving a better existence the disinterested play of thought, the power of dreams, the will to interpret the data of experience and to surpass ordinary experience. Even within what the world calls states of madness, an inner enduring force can be discovered. By accepting the demands of human desire, man can experience what has more reality than a logical and objective universe. One of the most original traits of surrealism, when one considers its contribution to poetry and painting, is the conviction that art is not an end in itself, that man must never stop with aesthetics and speculative philosophy.”

The language is old fashioned (eg., 'man' ) but the perspective is a fruitful one. Instead of using the old epistmological language I'll redescribe it. Surrealism is a way of knowledge based on desire. It is a knowledge of the world as lived by the body. An embodied knowing. Hence surrealism goes far beyond art, although art has been its most famous expression. It suggests a different way of relating to modern life to that of instrumental reason (eg., Taylorist and Fordist). It is a way of life based around a renewal of the sacred in everyday life.

We live in a world marked by nihilism; a world that has lost its cultural and communal cohesion as a result of the emptying out of our highest values. Hence we have the isolated individual in On Nietzsche and the isolated object in surrealist photography:

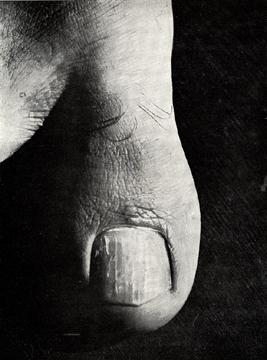

Jacques-Andre Boiffard, The Big Toe (1929)

Bataille saw surrealism as both a symptom and the beginning of an attempt to address this loss of meaning. Surrealism does this through a frequent transgression of a prohibition; through sacrificial rituals, self-mutilation (van Goghs ear), perversion and contact with the "animal in man."

Bataille's argument was that pure instrumental rationality (Comtean Positivism? ), and its offsprings Taylorism and Fordism (pure efficiency), left a gaping hole in modern life that was then filled with irrationality one way or another. The Surrealists responded to this situation by offering a way to express the desire for irrationality (such as excess, sacrifice, and fetishism) and by bringing the fruits of these irrational activities back to the realm of the rational within our everyday practices.

February 19, 2004

Bataille On Nietzsche#14

In chapter 5 of the second part of of On Nietzsche Bataille says that he presents:

'....evil as a means to use to "communicate." I've stated:"without evil, human existence would be enclosed in itself" or evil appears...as a life force.'(p.27)

Bataille then ties this to morality, which is what this part of the book is about. He says:

".... longing for the summit ---that our impulse towards evil--constitute all morality within us. Morality in itself has no value except as it leads to going beyond being and rejecting concerns for a time to come. Morality has value only when advising us to risk ourselves. Other wise its only a rule of interest."

This is very individualist conception of morality. It ignores the communal ethical life we lead and are a part of. Well, not exactly ignores. Bataille is hostile to ethical utility Hegel's idea of ethical life in the Philosophy of Right. (More here). This self-realization ethics directed towards the good life stands for conformity and represses freedom of the body:

"Sexual licence considered in relation to these ends [some comprehensible good] is almost entirely excess----a savage eruption towards an inaccessible summit--exuberance as essential opposition to concerns for the time to come."

Hence we have the heterogenous opposed to the repressive moral code of society.

February 18, 2004

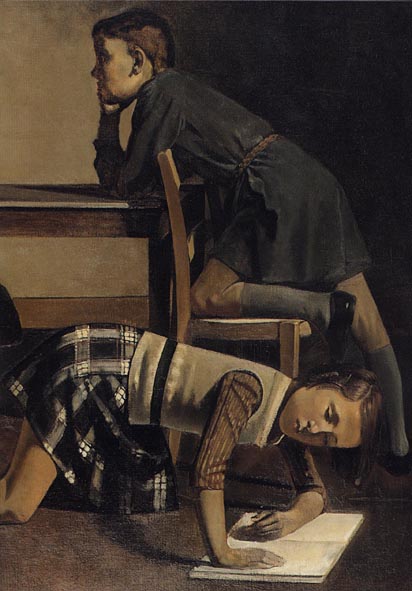

Wuthering Heights

I recently bought a little book called ‘Balthus In His Own Words’ (Balthus In His Own Words: A Conversation With Cristina Carrilo De Albornoz. New York: Assouline, 2001.) I have been long aware of Balthus’s interest in Wuthering Heights, which I have been inclined to see in Bataillean terms. Whether or not this is imposing something on Balthus that is not there I cannot say. In any case, it wasn’t until I’d been through this book that I realised how much Wuthering Heights had been a constitutive interest in his painting. I say ‘been through’ rather than ‘read’ because there is not a lot of text but plenty of illustrations, and it was from the illustrations that I learnt something of the constitutive role that Wuthering Heights played. I’ve collected a few books on Balthus and have seen a pretty good range of his work, but I can recommend this book because of the focus on Balthus’s Wuthering Heights illustrations. There are eight in all, which is more than any other book I have, and they give the reader a good sense of the significance of the book.

Balthus’s paintings are like book illustrations, a characteristic he shares with his brother Pierre. Pierre’s illustrations are largely of his own books. On this point I’d recommend The Decadence Of The Nude (Pierre Klossowski & Maurice Blanchot, London: Black Dog Publishing, 2002 – an excellent book with bilingual text), which has a good range of illustrations from The Baphomet and Roberte ce soir and The Revocation Of The Edict Of Nantes.

In saying that Balthus’s paintings are frequently like book illustrations, I mean that they seem to have a certain narrative quality, as if they illustrate a scene from a story. It is this feature of his work, I might conjecture, that has attracted the attention of a number of writers. I will say some things about these writers another day, particularly the fictional prose of David Brooks and the poetry of Stephen Dobyns.

But back to Balthus, his painting, and the general influence of Wuthering Heights. As the above illustrations show, an illustration of a scene from Emily Brontë’s book becomes a painting on an unrelated theme in Balthus’s hands. For me, it is not merely that a scene from the book might become another unspecified scene that perhaps isn’t from any book at all, although this possible feature is interesting in itself. Somehow, the mood, the atmosphere of Wuthering Heights, which Balthus captures so brilliantly, infects his painting as a whole. Let me draw a long bow and say that perhaps this atmosphere of Wuthering Heights, dark and brooding, childish and sinister, perhaps even evil, pervades all of Balthus’s painting. It’s a lot to get from one little book but that’s my experience, for what it is worth.

What does Balthus himself have to say about Wuthering Heights? In this book, not a lot, but what he does say is quite interesting – although I hope it doesn’t provoke an outbreak of Freudianism. He says:

‘I am a very emotional man, perhaps too much so… My youth was an absolute whirlwind of Feelings, exactly like Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, which I illustrated. I was completely at home in this novel. It described my youth perfectly. I was in love with Antionette – de Watteville – and I was determined to win her. But Antionette, on top of being a difficult girl, was already engaged to someone else. I reread her letters every evening. I think that, like Heathcliffe, I didn’t want to leave adolescence.’ (p. 14)

Balthus himself has said that it is wrong to attempt to psychoanalyse his paintings, although that didn’t stop the man he said it to from doing precisely that – but more of that anon (meaning: another day). For mine, it is better to look on what Balthus is doing from Karen Blixen’s perspective – that is, it is wrong to try to make a story into life; instead, the artist must make a story out of life. And that is exactly what Balthus is doing, in my book. He is remembering that he is a bit of a Heathcliffe in order to create art. His life provides the raw material. His paintings seem to tell a story because that is exactly what is happening. Elias Canetti got annoyed with the Bible because everything that happened to him was already recorded in there. Perhaps Balthus might have had a similar experience of Wuthering Heights.

Bataille On Nietzsche#13

In Chapter 4 of part 11 of On Nietzsche Bataille is concerned with communication. He says:

"Individuals or humans can only "communicate"---live---outside of themselves. And being under the necessity of to "communicate" they're compelled to will evil and defilement, which, by risking the being within temselves, renders them mutually penetrable each to the other."

In commenting on this Bataille quotes from a previous work, Inner Experience, to the effect that human life is more than an incomprehensible inner stream; it is also an opening to whatever flows out or rushes up to it. Hence there is limit to inner experience and a movement --'transgression'---over that limit.

So we can have a situation in which there is an incompatibility of Bataille's inner experience with what society recognizes as valid experience. From what I can gather in Inner Experience Bataille says that this incompatibility or gap plunged him into a crisis of meaninglessness. Bataille asserts the primacy and inculpability of interior experience as a way to resolve this crisis. Inner "experience itself is the authority even if that authority expiates itself.

So Bataille starts from the intense flows of inner experience only to the boundaries of inner experience are fluid and porous. Bataille finds that he is exposed to others, to events.

February 17, 2004

Bataille On Nietzsche#12

Our explorations of part 11 of On Nietzsche show that Bataille is concerned with the experience at the very limits of life, at the extreme where death impinges. On this edge, communication as physical lovemaking, as desire that takes nothingness as its object, comes into play. It loosens the boundaries of our individual monadic existence. It is the desire for flesh that leads us to risking ourselves by relating to one another. It is in sex that we find the complex interplay of communication.

Make no mistake. We are exploring the life of the flesh. Unlike Hegel, who concentrated on (embodied) self-consciousness to explore relatedness, Bataille concentrates on bodies. He is writing a philosophy of sex.

In Chapter 111 Bataille explores death. He says:

"What is disclosed in defilement doesn't differ substantially from what is revealed in death---the dead body and excreted matter are both expressive of nothingness, while the dead body in addition participated in filth. Excrement is the dead part of me I have to get rid of, by making it disappear, finally annihilating it."

Bataille links defilement to the obscenity of bodies, which derives from a disgust with excretion, that is put aside out of shame. He then says:

"Obscenity is a zone of nothingness we have to cross--without which beauty lacks the suspended, risked aspect tht brings about our damnation. Attractive, voluptuous nakedness finally triumps when defilement causes us to risk ourselves (though in other cases, nakedness fails because it remains ugliness wholly at the level of defilement)"

The theological language then intervenes and he starts talking about the defilement of temptation. He means temptation of the flesh: "under shameful conditions I give in ---and so pay for a streetwalker". His Catholicism means that this temptation eats away at him, torturing him:

"Crude obscenity gnaws away at my existence, its excremental nature rubbing off on me---this nothingness carried away by filth, this nothingness I should have expelled, this nothingness I should have distanced myself from ---amnd I'm left defenceless and vulnerable, opening myself to it in an exhausting wound."

A good expression of the inner experience of Catholicism.

February 15, 2004

On Nietzsche #11

Gary, I guess I understand what you are saying about the experience of flying (On Nietzsche #9) and how it might relate to some things that Bataille has written, but I must say that I don’t have those feelings myself when flying. As far as I’m concerned, I am more likely to die driving to Melbourne than flying there, but I don’t really think about it even when I get into the car. When I get on a plane I read, I eat the shit they pass out, I look out the window. My inner experience is one of boredom if anything. I don’t mind driving. When I’ve driven to Brisbane I feel like I could drive for ever. I want to keep going up the Bruce Highway. It’s as if you could just drive for ever, into an endless land, and at every stop something different, something new. When I get on a plane it’s to go somewhere and I do that to give a paper or see someone. I don’t like going somewhere for any other reason. You and I are pretty weird guys so the great mass of people are probably completely different from both of us, and we’re like black and white, like chalk and cheese, at least in some ways.

On Bataille’s Catholicism (On Nietzsche #10), in The Absence Of Myth: Writings On Surrealism, there are minutes of a discussion between, among others, Bataille and Klossowski. At one point Klossowski is asked if he agrees with what Bataille has just said. He says he does. Bataille is amazed, ‘since Klossowski is a Catholic.’ Klossowski replies, ‘You are a Catholic.’ Bataille: ‘I’m a Catholic? I won’t protest, because I have nothing to say. I can be anything you like.’ The conversation goes on to capitalism and post-capitalism, the efficacy of poetry, et cetera, before Klossowski repeats, ‘I have found you catholic at certain moments.’ Bataille responds, ‘I don’t feel in the mood to protest against being called a Catholic. If you say something completely without foundation, I will not reply.’ Someone else interjects, ‘I don’t consider you a Catholic but, rather, a Buddhist.’ The interjector says that Catholics place too much emphasis on the self whereas Buddhists regard the subject as an illusion. Communism and surrealism converge with Buddhism at this point. “that’s roughly what I’m trying to say, in a rather vague way,’ says Bataille. ‘Then you consider yourself a Buddhist?’ Bataille is adamant in response. ‘I don’t consider myself a Buddhist because Buddhism recognises transcendence… I feel closer to Buddhism than Catholicism.’ He’s not sure that communism and surrealism do converge at this point. With communism ‘there is a will to deny the person,’ he adds.

Bataille then goes on to say something that reminds me very much of the beginning of Franz Rosenzweig’s The Star Of Redemption, where it is stated that all abstract philosophy originates in the fear of death. Indeed it helps us forget this fear or cope with it, characteristically by banishing death from its realm of discussion. Talking about a post communist revolutionary world, Bataille notes that ‘a man like Rimbaud would have had as much reason to flee from a post-revolutionary world as the present world… Clearly the world as it could be after the revolution – the world in which, quite simply, there would no longer be anything to do except observe the world of the abyss, because all problems would be solved… In truth, it seems to me that man is bound by this fear, and to be separated from it is also the gauge of his affliction.’

Communism, as it is conceived here, seems to be rather like abstract philosophy, if it helps us to forget the abyss. What is the good of any such philosophy? The thought of Benjamin and Adorno doesn’t really make sense until it is recognised that this view drives their endeavours, this and the recognition that the radical atheistic subjectivism of people like Kracauer is also wrong. Indeed, this last is equivalent to the critical nihilism that Nietzsche criticises.

If I can just add an aside here, I’d like to add that in relation to Benjamin Foucault et al are regressive and represent a kind of contemporary positivism. No one who properly understood Benjamin could take up Foucault and find anything in it that represented a useful advancement. The French post-modernists as a group demonstrate an inability to understand the philosophy has reached, as it is represented in Benjamin’s writings. They are rather similar to Habermas in relation to Adorno. No one who really understood Adorno could think of Habermas as any kind of advance. Perhaps this is the real reason why Horkheimer was so opposed to Habermas. Of course, he was also suspicious of his role in the student movement of the sixties. Adorno also quite correctly regarded the student movement as fascist. We cannot simply blame the students for the present. They were duped by all the talk of new times and new ways of seeing, such like people in the twenties and thirties.

Back to Bataille (perhaps it should be ‘Bach to Bataille’): as you say, the abyss is other people, the radical other to our subjectivity, the nothingness at the limit of our individual existence. This is why fucking seems like a transcendent activity. It’s a desire and a fear at the same time. I never say to anyone, ‘I don’t want to know you. I don’t care who you are. I just want to strip you naked and fuck you. I want to crawl inside you and disappear.’ If they protested, ‘But you’re not treating me like a person,’ I’d never cry, ‘That’s right! I don’t give a fuck for you as a person. I want your body. I’m not interested in your mind.’ Instead of all this, I’d say, ‘How nice to meet you! What’s that you say? You’re interested in German aesthetic theory. I’d love to talk to you about that…’ In the beginning was the word and the word was with God and the word was God. In the end, no one believes that. In the beginning was the word and I curse it for fucking around with my life. In the end is silence, blessed silence, the silence of existence without the code of everyday signs, the silence of a thousand simulacra that talk to no one.

February 14, 2004

Bataille: On Nietzsche#10

We have seen that Bataille is concerned with the experience of the living on the edge; living at the very limits of life, at the extreme where death impinges.

In section two of part 2 of On Nietzsche Bataille defines communication as physical lovemaking, as desire that takes nothingness as its object. He sees sex as a form of sacrifice. He adds that sacrifice generally is associated with a feeling of crime; and that this sacrifice is an evil that is necessary for good.

It's all a bit of a puzzle, is it not? What does nothingness mean here? How is nothingness linked to sex? How is sex a form of sacrifice? What connection does sex as sacrifice have to do with the sacrifice of Christ?

Now Bataille does spell out what he is trying to get at here. He says:

'To clarify the links between "communication" and sin, between sacrifice and sin, I'll suggest sovereign desire eats away at and feeds on our anguish, on principle this engages us in an attempt to go beyond ourselves.'

The sin stuff is very theological and it reflects Bataille's Catholicism. Bataille converted to Catholicism in 1915, in a crisis of guilt after leaving his blind father in the hands of the Germans . It was Nietzsche’s work that lead him to abandon traditional religion for an idiosyncratic form of godless mysticism. The Catholic language remains 30 years latter.

Bataille says that the beyond of my monadic individual being is nothingness that is expressed in terms of painful feelings of lack. Those feelings disclose the presence of another person. Hence nothingness refers to the limit of an individual existence.

Bataille then says:

'Such a presence, however, is fully disclosed only when the other similarly leans over the edge of nothingness or falls into it (dies)."Communication" only takes place between two people who risk themselves, each lacerated and suspended, perched atop a common nothingness.'

Communication is each monadic individual reaching beyond the limits of their self-enclosed individual existence of I=I. This is pretty basic---a philosophical anthropology to use the academic jargon. Something that the sexblogs understand.

It reminds me of the beginings of Hegel's master slave dialectic in The Phenomenology of Spirit. It starts with two self-consciousnesses' posed in the element of externality. It is desire that opens up the moment of externality, or the reaching beyond the limits of the subject. The reaching beyond is a moment of relation. It is desire that drives the reaching beyond that leads to an encounter with another human being across the yawning gap or divide.

Does Bataille do what Michel Foucault’s asserts: that Bataille, “broke with traditional narrative to tell us what has never been told before”? Does Bataille tell us what has never been told before?

At the moment I see Bataille as working within the tradition of Hegel's master slave dialectic. He is rewriting it with a theological twist. The twist is sacrifice. Bataille says that his way of understanding:

"....gives a similar explanation to both sacrifice and the works of the flesh. In sacrifice, humans with a god by putting him to death; they put to death a divinity personified by a living existence, a human or animal victim....Sacrifice itself and its participants are in some waay identified with the ictim. So, as the victim is put to death, they lean to their own nothingness."

In both religious sacrifice and sexuality we have a leaning towards nothingness.

February 12, 2004

Bataille, On Nietzsche:#9

Trevor,

I've been in Canberra for most of the week caught up in the events of the moment. I just haven't had time to post, nor read what you have written.

However, I did read some Bataille's On Nietzsche on the plane over to Canberra on Monday night. I read the first six chapters of part two. I had hoped I would have been able to post, but I was too busy throughout the day. In this part we have certainly moved beyond the confessional accounts of Bataille's own internal experience of anguish with the war and destruction raging in Europe of part one.

And somehow the text made sense: the isolation of the individual, the difficulties of communication and death. So I will use that experience as my context for working through these chapters.

In the first chapter of this part Bataille turns away from the concerns of good and evil to consider the moral summit---excess or the exuberance of forces that brings about an maximium of tragic intensity. Decline means moments of exhaustion and fatigue.

In this chapter there is a couple of pages on Christianity, the crucifixation of Christ, it being an evil and criminals. It represents a summit of evil. Bataille then says:

'So clearly the "communication" of human beings is guaranteeed by evil. Without evil, human existence would turn in on itself, would be enclosed in a zone of independence. And indeed an absence of "communication"---empty loneliness---would certainly be the greatest evil.'

For Bataille communication is love, and love taints those whom it unites.

Sitting on the plane flying to Canberra on Monday night I certainly understood the existential state that zone of independence, lack of communication and the empty loneliness referred to. That is the normal experience on the Canberra shuttle plane. You sit in your seat shut up inside yourself trying to avoid the body space of those sitting next to you. This experience is an example of Bataille's "egoistic folding back into self."

Bataille then says that communication (ie love) involves placing this separate existence at risk. By risk he means being placed at the limit of death of and nothingness. The moral summit is the moment of risk taking. That is understandable on the Canberra shuttle plane. The boundaries of individual separateness is continually threatened by death---the very real threat of the plane crashing. It's on everyone's minds. Our bodies hang by a thread.

This normality is one of being placed at the limit of death. The risk taking on the plane is a stepping out of ourselves. On the Canberra shuttle that stepping out represents "being suspended in the beyond of oneself, at the limit of nothingness."

No doubt there are other ways of being placed athe limit of death----sex, sacrifice, criminality, illness, political destruction. But I did understand what Bataille was saying when on the Canberra shuttle on Monday evening.

It went after I landed in Canberra, checked into some rooms, went shopping in the supermarket, returned to the apartment to watch a bit of TV before collapsing into bed. I was no longer "suspended in the beyond of oneself, at the limit of nothingness." I was once again living within the boundaries of individual separateness: living as a monad where I=I.

previous next start

February 09, 2004

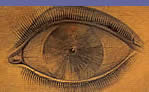

The Adelaide Accountant

Gary, here are the beginnings of a reply to your recent stuff relating to the eye:

The Max Ernst painting looks like an eye to me. I don’t know anything about its history either, but as far as I can see it’s just an eye. Isn’t the so-called ‘Cartesian eye’ a theoretical construction using the eye as a kind of metaphor, that is, a way of getting the theory? Do you know what I mean? The Cartesian eye isn’t really an eye at all. It’s a theoretical construction aimed at operationally presenting the world in a certain way. I’m thinking of Panofsky’s Perspective As Symbolic Form, where the Renaissance painting of say a battle scene isn’t ‘more realistic’ than the Bayeau (spelling?) Tapestry. Rather, it’s a way of selling the new perspective, the Euclidian story. It’s a kind of cultural induction, making use of something with which people are more familiar. In a similar way, we help people to pick up the idea of the periodic table by doing some things like mixing coloured liquids. This is said to take place in school chemistry laboratories. In actual fact, they are showrooms or little theatres. I’m getting off the topic. The point is, doesn’t the eye function in rather this way in the Cartesian story? Ernst’s painting doesn’t seem to capture anyone’s theory, Descartes’ or Bataille’s. Nonetheless, his Eye has a certain enigmatic quality typical of surrealism.

There seems to be a lot about looking in Story Of The Eye and it’s not just looking anywhere. The looking of concern is looking up women’s vaginas. This isn’t a peculiarly male preoccupation. Just about everyone wants to have a look up there. The question is, why? What is there to see in a vagina that there isn’t to see in, say, a mouth? Well, perhaps the mouth isn’t uninteresting in this respect either. In Gombrowicz’s Cosmos the mouth certainly takes on an erotic function of just this kind. I think Catherine Breillat has already answered the question: ‘The sexual organs of a woman are the doorway to the transcendent.’ Other people may disagree about this and think that it is wrong-headed. All the same, the view is that somehow through sex with a female it may be possible to escape the utilitarian order, even if only momentarily. This is the same as escaping the subject because the subject – the thing that so fascinates philosophers – is the bearer of the utilitarian order. This is sovereignty – casting off the yoke. It’s when I’m not being me, when I become an intensity without intention. That is why sleeping isn’t being in a sovereign state – because as Freud has shown, even when you are asleep you remain the bearer of the utilitarian order.

In Adelaide a few years ago there were a series of murders of young men. They died of massive anal injuries said to be inflicted by a mysterious group known as the ‘family’ and also said to comprise of a number of prominent figures in South Australian society. Eventually an accountant was arrested and found guilty of the crimes. It was reported that he picked up his victims, drugged them, and then ‘operated’ on their anuses, that he cut them open, that he dissected them. In short, they reckon he was a real pain in the arse.

This drive to dissect brings to mind an utterance by Marie, the heroine of Breillat’s film Romance. It one point Marie says, ‘I want to be opened up all the way, so you can see that the female mystique is a load of rubbish. I’d like to meet Jack the Ripper, he would dissect a woman like me.’

Bataille wrote:

‘There is nobility in your face: it has truth in its eyes, which you use to seize the world. But your hairy parts – those beneath your dress – are no less true than your mouth. Secretly do these parts open onto the world’s filth. Without them, without the shame that is always linked to their use, the truth ruled over by your eyes would be stingy at best.’ (Guilty)

If I understand this passage correctly, there’s a world ruled over by the eyes – the Cartesian world perhaps. There’s another world rules over by the hairy parts. The transcendent doorway is down there among them but it opens onto the world’s filth. That’s why, in the end, to use the Australian vernacular, the human being will be a filthy bastard. From this perspective, the eye is trying to muscle its way into the world of filth. But as soon as it does that it is dead, just like the priest’s eye that is inserted into Simone’s vagina, in Story.

This is the sort of thing that Barthes doesn’t really consider. His approach is a bit sterilised just when it should have been gloves-off. If Story becomes a poem then it doesn’t have any extra-poetic meaning, but it is no coincidence that it deals with the world’s filth.

It doesn’t need to sound as beastly as I’m portraying it. The world’s filth is another way of referring to the real day-to-day world, the order of blood and guts, the somatic realm, everything except the world of the mind. Only the mind is pure and wise, only the mind can look at the universal, the time-transcendent – so the story goes. But as Adorno - quoting Brecht - wrote, the mansion of culture is built of dog shit. There is no life of the mind that is free of filth. And every time the mind (eye) tries to master filth, filth masters the mind. Still, all this aside, as far as the eye going up the vagina is concerned, I’d like to try for a bit of transcendence in the here and now if that’s okay with you guys.

The Adelaide accountant isn’t much different from the people who believe in the transcendent power of vaginas. He thinks you can get there through the arse, but what’s the difference? (I think I’m going around the circles.)

I’ve been raving on and I’m sure I haven’t captured half of what is going on with eyes in Bataille’s writings, but I think you are right that it is something like the eye that looks through the lens of Newton’s camera (if that isn’t being too flowery). Once again, this is the problem with Barthes. Nonetheless, I think he did something really valuable in analysing and thus emphasizing the poetic character of the book. In so doing, he brings us back to the issue that keeps coming up in our conversations – that of the breakdown of the old literary genres in writing since the twentieth century.

February 08, 2004

Vision#6: The Cartesian Eye?

Max Ernst, The Wheel of Light, 1925

I cannot find anything about this image on the net. I came across it here.

Is it the Cartesian eye? Or Bataille's pineal eye.

How does it relate to a central conflict within our cultural history for primacy that has been waged between the book and the film, between the newspaper and the television, between the word and the image?

February 07, 2004

Bataille On Nietzsche:#8

Trevor,

It will take me some time to digest your article on Barthes' piece on Bataille's Story of the Eye (full text)

I haven't read too much Barthes as I found him too literary, too structuralist and way too formalist. He also said in 'The Photographic Message' (printed in Image-Music-Text) that the photographic image was "a message without a code". (p.17) In other words, photography is a transparent window on the world which readers then enwrap in a mesh of interpretations. Helmut Newton's body of work shows the strangeness of that view. The path of photography has been marked by a threefold relationship between the press and museums/art galleries and fashion/advertising. Photographs are just as interpretative as other visual arts, such as painting and drawing.

Whilst I digest your article on Barthes I want to briefly pick up on Bataille's On Nietzsche that I'd left off here. That last post finished with considering the last part of section one.

Now to consider section 2 of On Nietzsche which Bataille entitled Summit and Decline. It suggests a more theoretical consideration than section one, which was more about Bataille's inner experience. In his brief synopsis of section two Bataille says:

"The questions I want to raise deal with good and evil in reference to being or beings. ..there is the possibility that all morality might rest on equivocation and derives from shifts".

What does that mean? Bataille gives some indication by turning it inside out. He says:

"On the contrary, good relates to having contempt for the interest of beings in themselves....evil would be the existence of individuals --insofar as this implies their separation."

Thus we have an opposition or a contradiction. How is this to be resolved?

Bataille says that:

"Reconciliation between these conflicting forms seems simple: good would the interest of others."

Hence morality depends on equivocation and derives from shifts.

That's Bataille's overview of section two of On Nietzsche. It is hard to get much sense of what is going on. You can sense Nietzche in the backgroud with the genealogy of morality, the going beyond good and bad, and the critique of individual morality. So is Hegel, with Bataille's dialectical talk about opposition, shifts, reconciliation.

Here is my guess. The philosophical background to Bataille is Kant. Curtis Bowman gives a good description of Kant's philosophy. He says that Kant advocates the idea that we should become autonomous individuals who freely investigate the world in and around us without appeal to external authorities (whether they be human or divine). For Kant we become individuals who live freely by subjecting ourselves to the moral laws of our own creation.

Kant held that we are beings whose immeasurable value and dignity lies in our innate capacity for freedom of thought and action; that we are free beings who strive for autonomy. Autonomy as an achievement means that we are able to choose and set ends for ourselves and to develop the appropriate means to those ends. Being free but not autonomous is a condition Kant called heteronomous.

Our task is to become enlightened individuals who are truly autonomous, who choose and set ends for themselves and who develop the appropriate means to those ends. We are to do this in a way which respects the freedom of others, and so we are to act in ways that others can rationally consent to, thereby maximizing the amount of freedom in the world. As Kant sometimes puts it, we are always to treat others as ends and never merely as means as does instrumental reason.

February 04, 2004

more on the eye

Gary, I see you’ve been captivated by Bataille’s early writings on the eye and how these writings may represent an anti-Cartesian and even anti-Platonic approach to philosophy. It made me think of an essay I wrote a few years ago, actually four days after the famous September 11 event, although as far as I know it had nothing to do with that event. The essay briefly considers Roland Barthes’ essay on Story Of The Eye. Foucault also considers the book in ‘A Preface To Transgression’, which appears in a number of places, eg, Aesthetics.

On the topic of the role of vision in western thought, I was interested in your recent post on the windowless monad, in which you seem to suggest that Adorno’s thinking was rather like that of Bataille. The idea is that the relation of artworks to one-another is one of blindness. In Adorno’s words, they are ‘hermetically closed off and blind, yet in their isolation [they] represent the outside world.’ (You didn’t give a source.) Artworks ‘lead to the universal by virtue of their principle of particularisation.’

It seems to me that Klossowski provided a detailed account of this process in terms of the phantasm’s struggle with the stereotype. No doubt there are alternative explanations that are also useful.

Anyway, all this is just a poorly organised thought. What has always struck me is the closeness between Adorno’s and Bataille’s thought.

Here is me old essay on Barthes on Bataille:

Seeing Eye To Eye With Roland Barthes

* Pages numbers in brackets refer to Barthes’ article, if preceded by a ‘B’ they refer to Bataille’s book.

In the late 1960s, Calder and Boyars were prosecuted by the British government for obscenity because they published Hubert Selby’s book, Last Exit To Brooklyn. It was not until a second appeal that they were finally acquitted, so when Marion Boyars decided to publish George Bataille’s notorious pornographic work, Story Of The Eye she included two essays by distinguished critics in the hope that it would help in dissuading the censors from any thought of action. The Penguin edition, which appeared in 1982, contained the same content as the Calder and Boyars edition. One of the articles is by Susan Sontag. This essay, ‘The Pornographic Imagination’ deals with the question of pornography generally and argues for two distinct forms, one of which is artistic. The essay identifies Bataille as the leading representative of this latter genre. The other essay is by Roland Barthes and concentrates upon Story Of The Eye. It is this essay that I want to discuss here.

In a way that I will soon describe, Barthes approached Bataille from the perspective of style. Sontag noted that pornography of the artistic kind has a particular form. She quoted Adorno as suggesting that it is without beginning or end and does not contain the usual development and dramatic build-up of many other literary forms, such as the modern novel. This lack of definite beginning or end is precisely the characteristic of Story Of The Eye that Barthes found to be so central to his reading; in fact, he wrote of the book’s rhetorical structure being circular. Instead of a high point, it simply contains different points. Schematically, both pornography in general and Story Of The Eye in particular are of the following structure: ‘At one point during the sexual activity something in particular took place … and then the activity moved on to something else’.

In Story Of The Eye this basic structure is given a powerful poetic expression through an interplay of two interconnecting sets or series of metaphors, that of the eye and that of liquid. It is the results generated by this rhetorical play that give the novel its erotic character, according to Barthes. After I have described Barthes’ interpretation I would like to take up this point, which seems to be to be unwarrantedly abstract and formal in its conception. I will argue that the erotic character of Bataille’s book is also dependent on the pre-existing meanings of the terms employed. It is the relationship between this meaning and the book’s rhetorical style that is responsible for the specific erotic aura of Story Of The Eye.

Barthes could be seen as approaching Bataille’s book as a dialectician, for rather than employing that analytic machinery of surrealism as it has been formalised by post-modernists in terms of concepts like the simulacrum, he approached it in terms of literary polarity. But while he employed a dialectical method with one hand, he discarded it with the other, ultimately arguing for a purely formal interpretation as the only one admissible in this case. This led him to suggest that Bataille’s eroticism is but a consequence of technique.

The novels of the Marquis de Sade provided the foil against which Barthes was to counter pose as a strange kind of erotic prose-poem, Story Of The Eye tells the tale of an object rather than a person, an object that passes from image to image in a kind of migration, ‘far removed from its original being, down the path of a particular imagination that distorts but never drops it’. It is not simply a tale of an object that changes hands however and does not belong to that genre described by Barthes as a type of romantic imagination confined to arranging reality. What he called the ‘avatars’ in Bataille’s story, those earthly emanations of the divine, are completely imaginary and totally at odds with reality. While the novel form ‘makes do with a partial, derived, impure make-believe (mixed up with reality)’, Bataille’s story invokes ‘essence of make-believe’, a characteristic of poet expression. The novelist's imagination is probable, the poet's improbable. Poetic content can only ever exist in the realm of fantasy. While novels proceed by chance combinations of ‘real elements’, poems involve a ‘precise and complete exploration of virtual elements’ (p. 120).

Not satisfied by simply identifying of the opposing poles of novel and poem, Barthes proceeded to analyse Bataille’s story in terms of a number of linguistic and literary categories, which he arranged in dialectical oppositions: arrangement and selection, syntagma and paradigm, and metonymy and metaphor. The antecedents of all three dialectical pairs are related, as are the consequents: one is the path of arrangement, the orderly progression of statements, a transfer of meaning, the other of selection, of exemplars and particularly striking examples, of figures of speech that are not strictly applicable. How does all of this go together to provide Story Of The Eye with its particular erotic effect or aura?

Bataille’s book is surrealist in style, his notion of metaphor drawing on the ‘surrealist image as formulated by Reverdy and echoed by Breton.’ Reverdy’s principle was that ‘the more remote and right the relations between the two realities, the more powerful will be the image’ (p. 125). Barthes’ argument is that Bataille created this power of image through his metonymic manipulation of metaphor. Story Of The Eye utilises two chains of recurring metaphor, the eye and liquid, which are combined to great effect in a process further strengthened by a process of transference of meaning from one metaphorical level to another.

The object that is the subject of the book is the Eye, not an eye; an abstract rather than a concrete object. Barthes identified a number of fictional objects that represented the Eye, objects that were all similar in being globular, but also dissimilar in their uniqueness. This combination of similarity and dissimilarity is the necessary and sufficient condition for a paradigm. The first representation of the Eye is a saucer of milk in which Simone, the main female character squats. ‘Milk is for the pussy, isn’t it?’ says Simone (B p. 4) as she immerses her genitalia in the liquid. Another representation is the rear wheel of the bicycle that seemingly vanishes into the crevice of Simone’s backside (p. 32). Among such associations are a matador’s eyes torn out by a bull and a priest’s eye, which is inserted into Simone’s vagina. The eye of the narrator, which features in a number of scenes, is but another representation of the Eye. Such associations represent what Barthes called a ‘chain of metaphors’. In a literary sense, the chain of substitutes of the Eye decline throughout the tale, advancing like propositions of equal meaning, successive moments of the story of both endurance and variation (pp. 121-2). Whiteness and/or roundness provide for a declension of metaphors: a saucer of milk, the back wheel of a bicycle, eggs, particularly the yokes of soft-boiled eggs, a bulls’ testicles, the eye of a matador, the eye of a priest, the sun, the blind eyes of the father, the narrator’s need to see up the vagina.

The book’s other metaphorical chain involves liquid or liquefaction and is represented by a saucer of cat’s milk, by sweat, by steam, by sperm, urine, tears, and blood – the bowels of a gored horse spilled ‘“like a cataract” from its side’ (p. 122), even the sun’s light flowed like a liquid, providing a ‘soft luminosity’ and ‘urinary liquefaction of the sky’ (B p. 65). Another strikingly unusual case of liquefaction is ‘the milky way, that strange breach of astral sperm and heavenly urine … that open crack at the summit of the sky … a broken egg, a broken eye’ (B. p. 48). The sun is round and wet, hard-boiled eggs submerged in a toilet bowl are round and wet, an eye is round and wet, urine splashes on the eye of the narrator as he lies between Simone’s legs.

The power of Story Of The Eye comes neither from beauty nor novelty but is solely a consequence of rhetorical technique. It is ‘a kind of open literature out of the reach of all interpretation, one that only formal criticism can – at a great distance – accompany’ (p. 124). Metaphor cannot constitute a discourse on its own, however. Recounting its terms within a narrative structure forces paradigmatic elements to give way to syntagmatic developments. A paradigm is a kind of an infection that becomes an over-riding idea or image – Barthes suggested the example of soft-boiled eggs – but once stated a paradigm can only be reiterated and repetition does not constitute a story. Story of the Eye derives its narrative structure from the different combinations of its intertwining metaphorical series. In fact, Barthes maintained that the story itself is essentially an outcome of the need to express the inter-related metaphors in novel ways. For instance, a park at night is introduced ‘in order that the moon can emerge from the clouds to shine on the wet stain in the middle of Marcelle's sheet as it flaps from the window’ (p. 124), the visit to a bullfight is to extend the metaphorical play to a bull’s testicles and a horse’s intestines, the suicide of Marcelle to extend the metaphors to dead eyes that are urinated upon, and so on. The narrative is very restricted in this way, a feature that is much more characteristic of a poem than a novel.

Because the two chains continually touch interchanges are possible, the coupling a term from one metaphor with a term from the other, thus eyes weep, broken eggs run, light pours through the window, and so on. Bataille’s metaphorical couplings draw on moments everybody shares; Barthes described them as ‘ancestral stereotypes’ (p. 125). Bataille destroys traditional affinities, however. Instead of breaking eggs and putting out eyes, he writes of breaking eyes and putting out eggs. The images lie somewhere between the banal and the absurd but they are neither mad nor free images. In Barthes’ words, ‘In accordance with the law that holds that literature is never more than its technique, the insistence and freedom of this song are the products of an exact art that has succeeded in both measuring the associative field and freeing within it the contiguities of terms’ (p. 126), a process metonym as its organising principle. Thus the book contains expressions such as that of an ‘eye sucked like a breast,’ and ‘drinking my left eye between her lips.’ Bataille’s poetic technique utilises the single theme of each metaphor, so that:

by virtue of their metaphorical dependence eye, sun, and egg are closely bound up with the genital; by virtue of their metonymic freedom they endlessly exchange meanings and usages in such a way that breaking eggs in a bath tub, swallowing or peeling eggs (soft-boiled), cutting up or putting out an eye or using one in sex play, associating a saucer of milk with a cunt or a beam of light with a jet of urine, biting the bull's testicle like an egg or inserting it in the body (p. 126).

As a result, properties are combined and urination, ejaculation, tears and slopping share meaning through what Barthes has called ‘a technical transgression of the forms of language’ (pp. 126-7), the metonymy underlies syntagma, bringing about a ‘counter-division of objects, usages, meanings, spaces, and properties that is eroticism itself’ (p. 127).

In the one-dimensionality of Barthes’ analysis lies both its strengths and its weaknesses. His singular concentration on the stylistic qualities of Bataille’s prose-poem – the play of metaphor and metonym drawing paradigmatic expressions into syntagmatic associations – not only brings to the fore its peculiar and illusive literary properties but it also provides details of the role played by rhetorical style in modes of pornographic expression, effectively fleshing out Sontag’s observation. But like the logical positivists, he abandoned metaphysics in pursuit of his aims. As a result, nothing can be said about the role or reason for sexual activity in Bataille’s story; indeed he thinks that it is illegitimate to even ask such questions. In ‘A Preface To Transgression’, an essay on Bataille, Michel Foucault argued that it is not so much that sex finds a language of its own in pornography but rather that language does violence to sex, limiting its capacity to point beyond itself. This accusation could be justifiably levelled at Barthes in as much as his formalist account suppresses all such concerns. But doesn’t the Eye get its real meaning, its essential meaning from Bataille’s attempt to see beyond sex. If Catherine Breillat is right that sex is the doorway to the transcendental, then could Bataille’s Eye be seeking to look through this doorway? Isn’t this the real meaning of the book. Is it not this metaphysical idea that gives meaning and urgency to the books style? If the style of Story Of The Eye pushes beyond language – which seems an impossibility but Bataille was always in pursuit of impossibilities – this act gains purpose only through metaphysics. It cannot be reduced to a meaningless formalism.

February 03, 2004

Vision#5: Windowless Monads

Trevor,

your reference to Adorno's conception of an artwork as a windowless monad links back to the begining of modernity where folks like Alberti were talking about art and perspective in terms of transparent windows.

This was within a system of pictorial representation that rendered an illusionistic representation of reality within a balanced and harmonious order. This perspective system placed the eye of a man as the center of the world. It presupposed the work of art to be a transparent window which made a portion of the world visible to the viewer.

As I understand it---and I'm relying on memory here from doing a Donald Brooke course on aesthetics long ago--this system of pictorial representation meant a particular kind of perspectival vision. In this tradition perspective was akin to a reverse pyramid or cone, in which the apex was the eye. This visual convention----linear perspective---- centred everything in the eye of the individual beholder. So appearances flowed in from the things in the world to the apex eye, which was the vanishing point of infinity. The single eye of the spectator becomes the centre of the world.

The flow of appearances could only happen if there was a transparent and shatterproof window. Hence Alberti's window. The further assumption was that the picture would represent the visible world as if the artist were looking through a window.

Whilst here most cinematic representation is essentially the same as linear perspective. Marsha Adler says that as a way of viewing:

"Film perspective posits the camera's viewer's eye in a fixed position in space; the image is organized by and for the eye of the viewer placed in front of it. The image is posed, framed, and centered by the filmmaker to set the scene and to bind the spectator in place."

Even though I'm not sure what it means, I do understand that Adorno's conception of artworks as windowless monads challenges this perspectival visual tradition.

Here's a stab. First, the monad bit. If we return to Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz we find that in his monads v being self-enclosed. More specifically, for Leibniz windowless means that monads do not interact with each other. They exist in a pre-established harmony with one another.

For Adorno windowless does mean something along the lines of self-enclosed:

"In relation to one another artworks are hermetically closed of and blind, yet able in their isolation to represent the outside world...My argument is that precisely because artworks are monads they lead to the universal by virtue of their principle of particualization."

That's enough for me. The main point I wanted to make with this post was that Alberti's transparent window is displaced by the windowless monad.

next previous a href="http://sauer-thompson.com/conversations/archives/001397.html">start

February 02, 2004

Vision#4: Bataille's Rotten Sun

Bataille wrote several more articles that undercut the privileging of vision and the eye that I had noted here. They are 'Rotten Sun', 'The Jesuve' and 'Pineal Eye' (all reprinted in Visions of Excess). The last two articles, which are about an excremental fantasy, will be explored in another post.

In the earlier post I mentioned that this undercutting was part of an anti-Platonic turn in philosophy. The 'Pineal Eye' probably refers back to Rene Descarte's pineal gland, which Descartes argued was the key link between what our physical organs sense (eg. what our eyes see) and what our mind sees. Descartes' texts are full of visual imagery: sight is the noblest of the senses; what the mind sees clearly and distinctly are innate ideas; the valorizing of the fixed gaze of disembodied spectatorial eye; ideas as an image in the eye of the mind; the mind as a camera obscura; the sharp clear light of of the reasoning mind; there is a correspondence between our innate geometrical sense and the geometrical reality of the world of extended matter.

Hence we have the Cartesian perspectival tradition. It is a very pro-vision tradition premised on the sun of reason as the noble and the elevated.

This perspectival tradition is directly challenged by Bataille in the short 'Rotten Sun'. In this fragmentary piece the sun as the summit of elevation is equated with the sudden fall of unheard-of violence. Bataille says:

"The myth of Icarus is particularly expressive from this point of view: it clearly splits the sun into two----the one that was shining at the moment of Icarus's elvation, and the one that melted the wax, causing failure and a screaming fall when Icarus got to close."

Is Bataille endeavouring to bring about the fall of the Cartesian perspectival system through a hammering of the idols (Descartes/ the Enlightenment) now that God is dead?

The above myth illustrates the danger of too much enlightenment (illumination) and hence we have is the delirium of reason. Just as one can be blinded by looking directly into the illuminating sun the extreme point of illuminating reason opens the way to a certain blindness; Hegel's system has a blindness to non-knowledge, to the base materialism of dirt and filth, madness etc. The erotic literary works, such as Story of the Eye, explore this unassimilable base element in terms of obscenity and pornography.

Seeing - theory - cannot grasp its other (shit).

Hence the dethroning the eye in the Story of the Eye where uses images of eggs, testicles and the sun as symbols of the eye. Eggs are thrown into the air and shot at; raw bull testicles are placed into Simone's vagina and cause a brief orgasm; the ripping out of the matador Gratero's eye by a bull; the cutting out of the eye of the priest in the last chapter; the scene in the vestry of the church of Don Juan (the dead priest), where in the darkness Simone takes the enucleated eye of the priest and places it into her vagina.

As Daniel Brown says these images stand for "destroying the nobility of vision and reclaiming the base ecstasy of the dark natural world."

I have come across this passage from the Story of Eye in an artivcle on Bataille and cinema by Don Anderson. The passage highlights the code at work in Bataille's text: