March 30, 2004

Heidegger & Nietzsche: the end of metaphysics

Trevor,

The month of contract work is finally drawing to a close. I have to be quickas we are going for a late dinner in Kingston as a way to unwind from a hectic month of the autumn sitting.

Heidegger's key argument against Nietzsche is that Nietzsche did try to overcome the western metaphysical tradition. He broke with platonism and representing the one true world. This is what the postmodernists mean by Nietzsche's destruction of metaphysics--ie., dancing on the grave of metaphysics.

This rupture with the one true world of Platonism opened up a Heraclitean world of flux, stripped of stability, purpose and predictability. Thus life becomes a terrifying and tragic experience amid the constant flux of becoming (Delueze's starting point, if you like.) As there is no moral redemption in a Heraclitean world sufering becomes a means to life's affirmation.

But in rupturing with Platonism Nietzsche, from Heidegger's perspective, became caught up with its subjectivism. That is the crux of Heideger's argument against the ethics of the sovereign individual creating itself anew. Ethics (with its liberation from ends) becomes an experiment (of sacrificing ourselves and letting ourselves a go) not a contract. That is where Foucault's ethics start. What Heidegger sees is the metaphysical residues of the humanist tradition, or a reinvestment in metaphysics as he affirmed the value of life through risking all in the adventure of testing, displaying, self-creating anew and achieiving greatness through our deeds.

But more is involved in Heidegger's argument than this. Nietzsche, the harshest critic of Western culture in the history of philosophy, celebrates the that culture's most cherished value, freedom. Nietzsche, for Heidegger, marks the culmination of metaphysics. This metaphysics had reached its end: it had reached a historical moment when the essential possibilities are exhausted.

By this Heidegger meant something similar to us saying that the analyic tradition has exhausted its possibilities.

For Heidegger Nietzsche's individualism amounted to homlessness --a nomadism--it is the furtherest point in an individualist and subjectivist metaphysics. Nietzsche is no postmodern visitor to metaphysics who might shake the dust from his feet. He is a permanent guest in t e hosue of modern metaphysics.

Heidegger's confrontation with Nietzsche in the lecture course is based on attempting to "grasp Nietzsche's philosophy as the metaphysics of subjectivity." In this confrontation Heidegger showns that in constantly wrestling with individualism and subjectivism---it is the curse, poison and idol of modernity--- Nietzsche cannot do without its support.

March 29, 2004

Heidegger & Nietzsche

Trevor,

It is late in Canberra. It has been a hectic day and I only have the energy for a some quick remarks.

Two quick points. One way to explore the issues you raise about Heidegger is to turn to Heidegger's lecture course on Nietzsche during WW2. In this lecture course Heidegger struggles with Nietzsche, and he sees Nietzsche's philosophy as the metaphysics of subjectivity that reinforces, and works within, the humanist tradition.

Nietzsche's text abound with a heroic individualism of the sovereign individual (overman) who raises himself above his culture and who invokes a pathos of distance separating the individual from the herd. These higher types who revalue our values in a nihilistic world are homeless wanderers accompanied by their shadows. At best they hope for a home in a future world. For Heidegger the concern is find a home in the technological world of today.

The other point I want to make picks up on your What is philosophy post. If we turn to Heidegger's Letter on Humanism we find remarks to the effect that modern metaphysics is based on the duality of subject and object and conceals other ways of thinking about our being-in-the-world. he says that must free ourselves from modern metaphysics and its technical interpetration of thinking and its determination of knowing as theoretical. He then remarks that since the advent of modern metaphysics:

"..."philosophy" has been in the constant predicament of havign to justify its existence before the "sciences." It believes it can do that most effectively by elevating itself to the rank of a science. But such an effort is the abandonment of the essence of thinking. Philosophy is hounded by the fear that it loses prestige and validity if it is not a science. Not to be a science is taken as a failing which is equivalent to being unscientific."

That pretty much sums up the ethos of analytic philosophy that I was trained in and struggled against. Thinking was formal logic, philosophy was mostly about the metaphysics and epistemology of science (fundamental physics), there was no shortage of attempts today to reduce the human being to neurological processes and hermeneutics was dismissed as nonsense. Philosophy was about science, period.

One can speak (disparagingly) against that scientific conception of philosophy as I do and still speak in terms of the philosophical tradition that thinks otherwise to the analytic mode of philosophy.

March 28, 2004

Heidegger again

Gary,

I’m going to be away until Thursday, so if you don’t hear from me that is why. If you can manage the fort until then it would be great.

I know that it’s pretty much the received view that Heidegger’s politics were rotten but the rest of philosophy is okay, if not brilliant – the best thing to come out of the 20th century, but I want to disagree with everything in this claim if for nothing more than the sake of discussion.

Certainly, the view I was trying to represent – I won’t name the persons to whom I refer because I may not be getting them right – is one of an existentialist philosophy, there’s no doubt about that, that emphasizes what we might call ‘enabling’ (I don’t want to get into jargon) as constitutive in seizing the crucial moment that will allow one to enter into what might be called ‘authentic’ existence – i.e., in which you own your existence and it is not a slave to external forces. Existentialism is about completeness – man want to be God, says Gombrowicz says. If I’m getting the Heidegger story right as my storyteller is telling it, then want I want to argue is that if this is your approach to the world, then it could easily seem that fascism is offering the possibility of just such a moment.

I want to sum Heidegger up, not judge him. Karen Blixen taught me this distinction. I want to know where his philosophy ultimately goes. If it doesn’t go where I’m describing then I want to know where it does go. If you know, please tell me. It’s no good if I’m living under an illusion.

As far as existentialism goes, the brute I’ve described above, I’m with Gombrowicz and Bataille: humans seek incompleteness, rather than completeness. Ansell Pearson calls this a ‘superior existentialism’ (have a look in the library for this article). I’ve been calling it ‘surrealism’, for want of a better description.

Before I could judge Heidegger I’d have to ask myself what I might do, particularly as a young man, if I suddenly found myself the vice chancellor of a university in the middle of an anomie-creating period in history. I’d be the biggest fuckwit to ever grace the stage. Who knows what stupidity I’d blurt out before anyone could stop me. Shit! Afterwards I’d look a real bunny. War crimes, crimes against humanity, crimes against nature, the whole bang and caboodle – anything’s possible. Please, try to remember that, in the end, I am like a child in this world. (I’m starting to sound like a Christian.)

We must always remember that the individual is never to blame. George Bush is a human being, just as Adolph Hitler and Joseph Stalin were individuals, or Saddam Hussein, et cetera. This applies to anyone who like to think of. We should weep to see what happened to them. We should weep for the terrorists, who have got things so wrong. There is no point in killing them or anybody else.

Once again, I agree with Gombrowicz: our struggle is with form. We have a terrible problem with organisation, with administration. All the crap about morality flows from it. Deleuze called it a problem of territorialisation the idea is his greatest contribution to our way of seeing the world. We are overwhelmed by this form that tries to form us. The other night one of the women in the reading group said that she felt so ignorant and I suddenly felt ashamed of myself because I had been the tool through which form had overwhelmed this person. According to Gombrowicz, when this happens we construct a refuge for ourselves out of the refuse of higher culture, a secondary domain of compensation, and it is here that a certain compromising beauty is created, a certain shameful poetry. We have entered the realm of pornography. But who thinks that the administered world is anything other than obscene? That’s the trouble with the place you keep going to in Canberra: it’s the administrative stage on which the infantilised are let loose. Mephistopheles is the director.

March 27, 2004

Heidegger: poetics is a key

Trevor,

Poetics was not an ornament for the post-Being and Time Heidegger. Poetics meant Holderlin. Heidegger went on and on about the Germans needing to understand the historical significance of Holderlin's poetry. It stood for, or signified, a great turn, a national awakening for Germany.

Poetics was the core of Heidegger's late philosophy--the one developed after his engagement with Nietzsche.

Holderlin's poetics shaped the way Heidegger's philosophy engaged with politics. Germany's future lay with a going back to the Greeks as a way of moving beyond liberal capitalism and Soviet communism through the creation of a national language.

March 26, 2004

The Heidegger affair

Okay, so Heidegger's politics was German fascism. And he never faced up to Auschwitz after 1945. He just maintained a determined silence about the extermination of the Jews.

He is to be condemned for that. It is an unforgiveable silence. And Heidegger is to be condemned for his evasions after 1945.

Is that the end of the matter with Heidegger? I ask the question as philosopher, since that it is what I am, and it is the tradition that I work within.

To say yes implies that a philosopher's work can be reduced to his politics; or that Heidegger's philosophy leads to this kind of fascist politics. Or that the essence of Heidegger's philosophy is that which corresponds to his fascist politics and every else in his philosophy is ornament or superfluity.

So the question concerning Heidegger is the question concerning Heidegger's Nazism.

Fair enough, if you want to devote your energies exploring that vein. Let me say that Heidegger was not a reluctant liberal joining the National Socialist Party to defend the freedom of the university. Heidegger was not a liberal who defended the parliamentary democracy of the Weimar government, nor did he join the Party to defend the academic freedom of the university as it then existed. He was a radical conservative.

However, this way of approaching Heidegger through his politics does remind of people in the 1970s in Australia condemning Hegel's philosophy because he was a conservative, the philosopher of the restoration who supported the Russian state. The implication? One should not read Hegel because he was a conservative.

Most of them were analytic philosopher who thought that Hegel's philsophy was the pits. How did they know? They had read Bertrand Russell's tabloid History of Western Philosophy. Bertie was the bees knees in those days.

It is similar scenario with Heidegger.

I read Heidegger differently. I initially read him through both the late turn to ecology and his early turn against the modern philosophical tradition. What he says in both phases is important and significant in terms of both the re-writing of modernity and the development of another kind of thinking to that of science and technology.

March 25, 2004

What is Philosophy?

Gary,

It’s not a bit rough on Heidegger. I don’t care what he says about instrumental reason or technological enframing, or poetics – all existentialists say a lot of useful things on a lot of topics. The issue in the end is what is it that they say, what is about existentialism, that is wrong, fundamentally wrong?

On this score you can’t see the wood for the trees. You speak disparagingly of philosophers but you typically conduct yourself just like one. Some of the very best philosophers I have come across can appreciate every faded and delicate nuance of the most intricate and complicated of thoughts. They are the experts – the Hegel experts, the Nietzsche experts, the Foucault experts, the mahjong experts, et cetera, et cetera, onward, for ever onward. The only thing the experts can’t tell you is where they ultimately stand in relation to these ideas.

Let me quote some Georges Bataille for you:

‘Anguish only is sovereign absolute. The sovereign is a king no more: it dwells low-hiding in big cities. It knits itself up in silence, obscuring its sorrow. Crouching thick-wrapped, there it waits, lies waiting for the advent of him who shall strike a general terror; but meanwhile and even so its sorrow scornfully mocks at all that comes to pass, at all there is’ (Madame Edwarda, et al, p. 147).

Here is the true path of philosophy: ‘meanwhile … its sorrow scornfully mocks at all that comes to pass, at all there is.’ Philosophy is dissatisfaction with every idea, with all that is, with all that comes to pass. The idea is precisely to be a bit rough with people like Heidegger, and to be dissatisfied with his thought in a fundamental way. This is one of the great things about Russell – he risked unfairness for the sake of dissatisfaction. And that’s what Dorothy Green can see in him, in his words, regardless of any odious philosophical baggage. It’s one of the great things about Dorothy Green. You should read her. It’s worth it.

You have to do philosophy this way or otherwise you are a convert, a disciple. Who wants to be one of those? As Canetti said, if you want to follow Kant then be like him. Kant was critical of every other view, scornful, mocking, or at least he aimed to be. Become a Kantian – fill yourself with scorn.

We can go on with some endless bullshit about the brilliance of Heidegger but it won’t get us anywhere. In the end it is a question of what is at stake, and that’s what I was talking about in my last entry.

Adorno has nothing to do with my account of Heidegger. I’m talking about my views and not Adorno’s. As far as Adorno goes, he’s wrong like everybody else.

Actually, I’m not even talking about my views but about material that may be presented at the conference, both the presentation and how I’m going to come back at it during the discussion. When someone talks about ‘enowning’ – I think that’s the word Heidegger uses – and the ‘crucial moment’, I’ve got every right to come back at them by saying that I can see how someone who thought this way might get sucked in by National Socialism.

This is an important question because lots of ordinary decent people got sucked in by National Socialism and we need to understand why. It’s absolutely crucial. Indeed, this is the most crucial issue of all, in the midst of a world in which, to quote Benjamin, ‘fascism has never ceased to be victorious’. The interesting things Heidegger had to say about poetics are irrelevant compared to this question. I also think I’ve got a right to say that he appears more stupid than he actually was – after all, he did get sucked in by National Socialism. That makes him some kind of fuckwit in my book.

March 24, 2004

Heidegger distortions

Trevor,

That's a bit rough on Heidegger. You read him through Adorno. You do not read Heidegger's texts.

He explicitly rejected the existentialist reading you attribute to him.

Nothign on instrumental reason as a technological enframing.

Nothign about Heidegger's texts on poetics or art.

Nothing about undermining the dualities in western philosophy.

Nothing about philosophy as interpretation---what he has in common with Adorno.

March 23, 2004

Philosophy Conference

Gary, I haven’t written anything for awhile for a number of reasons, among which, I’m in the process of changing my internet provider and am restricted in the time I have available, and W. has gone o.s. and left me to look after the conference for six weeks. It’s been a bit of a tangle that has taken some time to work out. I’m starting to get somewhere I think.

I’ve read everything you’ve written lately and I must admit that I don’t know how to reply. Perhaps I’m just tired. I haven’t been sleeping well lately for some unknown reason. And maybe some of it is just too hard to reply to. Firstly, there’s the stuff on Bataille. I’m a bit distant from all that at the present moment and anyway you often just chuck in some elliptical remark that can be as obscure as Bataille’s original. Somewhere you say something about Bataille overcoming death, if I get you rightly. I don’t think Bataille wants to overcome death. I think he wants to embrace it. ‘The trouble with death,’ he says somewhere, ‘is that it only lasts for an instant.’ This sort of remark suggests that its not overcoming death that he’s interested in, but something else, something altogether different.

I won’t go on with this. Instead, I think I might tell you about the conference. Who knows, it might attract some participants. One of my jobs is to put the program together, after wresting abstracts from those who offered papers, just to make sure they’re coming. Believe me, it’s like pulling teeth. But I’m getting somewhere. I’ve just about got a full program. It goes like this:

Remember, it’s called ‘Messianism, Apocalypse, Messianism and Redemption: 20th Century German Thought.’ Papers offered cover three broad areas: philosophy, theology, and literature. The problem is to sort them into some kind of useful order. At present, the plan is that they go like this:

Two keynote addresses will aim to give a broad introduction to apocalyptic-messianic thought in philosophy and culture generally, and in theology.Then I’ve got four papers under the provisional category of ‘general background’, on Ludwig Klages, the Stephan George Circle, German expressionism, and Karl Barth, who advocated a kind of historical Christianity (I hope I don’t offend anybody with the carelessness of my words). The next category is broadly existential, in the sense that Bataille gives this word. Under this heading there are papers on Rudolf Bultmann, Franz Rosenzweig, Martin Heidegger, and Karl Rahner. Rahner seems a bit out of place here and may end up some place else. As a kind of anti-existentialism, there are four papers on Ernst Bloch, Siegfried Kracauer, Walter Benjamin and Theodor Adorno. The next category is large and not so well organized. I’ve called it ‘the following generation’. It includes papers on Gerhard von Rad, Wolfhart Pannenberg, Gunter Anders and Karl Jaspers, W.G. Sebald, Jurgen Moltmann, Gunter Grass and Erich Kastner. Papers have been promised on Buber, Tillich, Metz, Hildesheimer and Bonhoeffer but I haven’t seen the abstracts yet.

I’m most interested in the story involving Rosenzweig, Bloch, Kracauer, Benjamin and Adorno. It’s the most unique and peculiarly 20th century of all the stories, in my view. The theologians Metz and Moltmann interestingly take up this strain, while there is a tendency in late 20th century philosophy to neglect it in favour of a kind of Habermasian liberalism or post-modernist anti-liberalism. The Benjamin-Adorno philosophy is a distinctively different approach to either of these two.

In an effort to wet some appetites, I’ll try to tell the Heidegger story as it might be presented at the conference.

One of Heidegger’s most important concepts is that of the ‘decisive moment’, which is a ‘moment of vision’ that is not reducible to mere eyesight or to a sudden occurrence in time but, rather, represents insight, a moment of vision. These are rare events and must be sought after and discovered. For Heidegger, this is one’s project of Being. The notion allows Heidegger to avoid giving primacy to non-theoretical immediate experience. This seeking redeems Dasein from lostness in the everyday, because it requires a fundamental or authentic ‘attunement’ to essential possibilities. The decisive moment is related to owning one’s experience.

It’s easy to see how this philosophy can lead one into all sorts of awkward predicaments. Dear old Martin saw the early 20th century as chockers with these decisive moments and he was wracked with anxiety in case he missed the crucial event. When you couple this with his idea of providing a radical new philosophy underscored by the everyday situation of Being-in-the-World, Blind Freddy can see where it’s all heading. The project becomes to redeem Being from its ‘fallen’ state and the restoration of its ownership of experience. This isn’t just a subjective thing but involves the transformation of all beings into ‘coming future ones’. When Martin saw the Nazis as the coming future ones he was just following the philosophy he’d developed. To borrow from Benjamin, you could say that Martin listened hard to tradition and those who listen hard do not see, except it wasn’t tradition he listened to but his own ravings, inspired by a dose of Kierkegaard and a dash of his own particular brand of Nietzsche – everybody has their own brand. It’s the cave of a thousand Nietzsches. In Nietzsche’s house there are many palaces – who was it that said something like that? Oh yes, the Christians. It’s one of their favourite lines.

Heidegger wasn’t a very good Nietzschean. When Nietzsche said that philosophers always appear more stupid than they actually are, Martin didn’t understand what he meant and so he became one of the stupid ones and invented a philosophy that, in the name of direct experience, provided something to stand in the way of direct experience. Existentialism is just another form of nihilism in Nietzsche’s sense. It’s what Adorno called the ‘jargon of authenticity’.

March 22, 2004

Bataille: On Nietzsche#19

We have come to chapter 9 of part 2 of On Nietzsche. In it he addresses the summit's link between a mystical state and impoverished existence. Bataille says:

"Solitary ascetics pursue an end whose means is ecstasy ---and ascetics work for their salvation like merchants buying and selling wth profit in mind or like workers sweating for their wages....As for ascetics: by falling into common human misery, they become obsessed by a possibility of undertaking the lengthy work of deliverance."

I'm not sure what to make of this. It is pretty cryptic in terms of the connections between ascetics and merchants.

I'd always though of ascetics as being in opposition to merchants. None of this is making much sense to me. I just cannot make sense of the book.

next previous start

March 21, 2004

Nietzsche, Bataille & a declining life

Trevor,

I'm off to Canberra tonight. So this is just a short note. My posting will probably be light over the next 4 days.

The recent entries on Bataille about the path to spirituality and the morality of decline reminds me of Nietzsche's ideas about a declining life.

Declining life for Nietzsche represents a reduction in vigor and capacity to enrich life. It contributes to a decrease in life.

Nietzsche contrasts this modality with an ascending life (Bataille's moral summit), which represents an incrment in vigor and capacity to enrich life.

An example of a declinig life is a life devoted to altruism which he sees as an example of slave morality based on self-denying value.

Bataille is working within the horizons of Nietzsche's genealogy of morals.

March 20, 2004

Bataille: spirituality & the morality of decline

Since Caravaggio is flavour of the month in Australia I thought I might introduce his images into Bataille's discussion of the sacred in On Nietzsche.

In chapter 8, part 2, On Nietzsche Bataille is working within Nietzsche's category of decadence, which he reworks in terms of decline.

Caravaggio, The Ecstasy of St Anthony, 1595

The sexuality of boys is incorporated into sacred art, which is the realm of the good, which is the primacy of the future over the present.

It also illustrates Bataille's thesis that the pathway to spirituality, through the resistance to temptation, belongs to exhaustion and fatigue. It is a part of the morality of decline. Bataille reasons in chapter 8, part 2, On Nietzsche thus:

"When we feel our strength ebbing and we decline, we condemn excesses of energy in the name of some higher good. As long as youthful excitement impels us, we consent to dangerous squandering, boldly taking the risks that present themselves. But as soon as our strength begins to ebb or we start to preceive the limits of this strength (when we start to decline), we're preoccupied with gaining and accummulating goods of all kinds... since we're thinking of the difficulties to come."

Now the spiritual summit ---which opposes sensuality and pits itself against it---is associated with efforts that desire to gain some good.

Hence the spiritual summit no longer comes with the horizons of a summit morality of excess (exuberance and tragic intensity). It is within the horizons of a decline morality.

previous start

March 19, 2004

Bataille: On Nietzsche#18

In Chapter V111 of Part two of On Nietzsche Bataille says that what is needed to reject sensuality, temptation and being an easy prey to desire in order to take the path of spirituality is consideration of time to come. He says:

"...we escape a giddying sensuality only by representing for ourselves some good situated in a future time, a future that sensuality would destroy and that we have to keep from it. So we can reach the summit beyond the fever of the senses only provided we set a subsequent goal."

Bataille says that another way of saying is this is that resistance to temptation of sexual desire implies abandoning the summit morality. This resistance belongs to the morality of decline.

What does this mean?

If we return to chapter one of part two of On Nietzsche we find Bataille saying that the moral summit is different from the good. Decline determines the modalities of the good. Bataille says:

"The summit coressponds to the excess, to the exuberance of forces. It brrings about a maximium of tragic intensity. It relates to measureless expenditures of energy and is a violation of the integrity of the human being. It is thus closer to evil than to good."

In contrast the decline corresponds to the moments of exhaustion and fatigue. So the pathway to spirituality through the resistance to temptation belongs to exhaustion and fatigue.

March 18, 2004

looking at death in the face

I'm stilll struggling with Bataille's On Nietzsche. It is a very elusive text. I've just decided that I've been coming at this text all wrong.

I don't mean that I want to jettison the Hegelian phenomeological structure of reaching out to another through the breaching of individual self-suficiency. Rather the text is more basic that the core of Hegel's dialectic of master servant ---ie; the desire to reach out to another from one's inner experience.

Sure, that is how Bataille talks. But underneath this talk is something more basic/primitive/existential: it is Hegel's conception of life depending on death. If you like Bataille is looking at death in the face and tarrying with it. Bataille's text is a confrontation with, and an overcoming of, death.

I had got it with my experience of the flying on the plane to Canberra. Flying is all about death. It is a tarrying with the negative of life. But I forgot the death part of that experience and only remembered the reaching out to others.

March 17, 2004

a half education

Trevor

I'm too tired to post much. So a quick point. The Weak Thought post over at Spurious captures part of my experience. Lars says:

"When I worked in Analytic departments, it was a great struggle to be able to teach Husserl – teaching Heidegger or Merleau-Ponty would have been unthinkable; ‘continental’ thought was not deemed philosophical. It was worse when I was as an undergraduate: we were presented with no post-Kantian ‘continental’ thinkers at all, which means no Hegel, Schelling, Marx, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty let alone Foucault, Deleuze, Derrida and others."

We were luckier here. We managed to read Hegel and Adorno and Nietzsche and Heidegger, even if we could not teach them within a philosophy department.

But I too am ever conscious of the superficiality of my grounding in the Continental philosophical tradition.

Update

The little knowledge that I do have would give Nietzsche a central place in this tradition. It was Nietzsche who undercut the struts of the philosophical enterprise: the search for Truth through Science to achieve the one true account of reality. This is what contemporary physicists called the Theory of Everything: a set of equations that could be written on the back of a t-shirt. Russell still had a big faith in Science and a Theory of Everything that would enable a fundamental physics to know the universe completely.

If we knew the position and velocity of every particle in the universe, and understood the laws of physics that governed them, we could - given enough computing power - work out the state of the universe and everything in it, at any time we chose. So powerful would the equation be that, to know it, would be to know the mind of God.

Russell looks so conservative when placed alongside Nietzsche, who sought to demolish the idol of Science. Nietzsche is dynamite. A lot of continental philosophy is a coming to terms with that explosion.

March 16, 2004

Bataille: On Nietzsche#17

Trevor,

I did manage to find a clear spot for a moment today. My thought? I will use Bataille as a centring text, spin out from there in different directions but keep coming back to Bataille.

What I would like to put on the table is that we can understand Bataille's thinking otherwise to utility in terms of Weber's conception of modernity as the process of rationalization and the hegemony of technology as a way of thinking (economic/techological rationality).

Utiltity stands for this cconception of modernity.

The turn to the sacred and Christian ecstasy is a way of thinking otherwise. This ecstasy was propelled by desire. However, this desire did not lead to sexual orgies. As Bataille writes that with religious mysticism:

"Meditational subjects have taken the place of real orgies, drunkenness, and flesh and blood---the latter become subjects of disapproval. In this way there still remained a summit connected with desire."

There is also a communication with a beyond of oneself that is based on a wounding or tainting of ourselves.

March 15, 2004

the spectacle

Guy Debord in the Society of the Spectacle says the spectacle is not just a collection of images; rather it is the social relationship between people that is mediated by images. In all its manifestations--news, propaganda, advertising and entertainment--- it epitomises the prevailing mode of social life. It is a self-portrait of power.

There is an interview with Henri Lefebvre by Kristin Ross on the Situationists and Guy debord over at Spurious The situationists in the 1960s appear to be very similar to, and a continuation of the surrealists in the 1930s.

March 14, 2004

a surrealist moment

Just to lighten things up a bit.

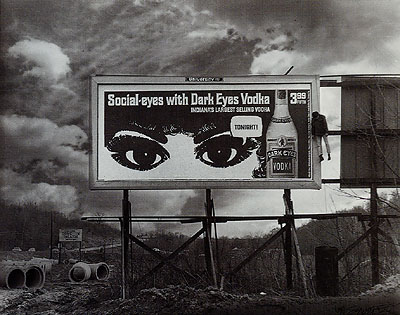

Jan Saudek, Social-eyes with Dark Eyes Vodka, 1969

I lead a nomadic existence these days within the changing state of things. I live in a volatile juncture within a disparate set of circumstances that are forever changing. The image caught my eye as I was moving through the differently ordered centres of the legislating subject.

Dunno what I thought when I saw it. The eyes of surveillance; the society of the spectacle; the difference between force and power; the wildness of chaos that breaks constraints and walls; a nomadic space that Nietzsche called a gay science; myself as a dynamic life force moving through space; a pitch of intensity.

Bertrand Russell's philosophy was all about system---an architecture of propositions constructed in terms of mathematical axioms. I much prefer philosophy as a tool box whose tools can be used a crowbar to pry things opne or a hammer to sound out their rottenness.

March 13, 2004

a note on rhetoric & politics

Trevor,

you have been doing a great job keeping things going here whilst I've been away slogging away in the political machine in Canberra these last two weeks. I've reached the point of complete exhaustion. The machine sure sucks one's life energy away.

There is no spectatorial detachment from the world there in that chaotic flow. I reckon you could start a bastard kind of philosophy from within the machine; one that is a far cry from that of the bureaucrats of pure (scientific) reason who speak in the shadow of the despot and are in historical complicity with the liberal state. Theirs (eg., the philosophy of Bertrand Russell) is a world of good sense, stable subjectivity, rock-like identity, universal truth and white male justice. It fits snugly with the requirement of the established order.

Russell the person was another matter. A radical. But that radicalness was never expressed in his philosophy. He was too enamoured of science and mathematics. Hence the Schizoid character.

I agree that the politics in Federal Parliament is, and should be seen as, theatre:

Bill Leak

It is theatre for the television cameras that beam the images across the nation. It's an integral part of the society of the spectacle.

True, politics also works in terms of deals being cut in the backrooms away from the democratic gaze. Then the deal has to be sold to the electorate. Hence the importance of rhetoric in the form of the press conference and media release. It's selling the image after the deal has been made.

Good political cartoons are a form of rhetoric that seek to persuade. So too are most of the speeches and media releases of the politicians engaged in policy making, and the commentary by the top journalists. These are different forms of rhetoric that seek to persuade people to adopt a particular course of action.

I would resist the reduction of rhetoric to propaganda. Rhetoric used to be a part of philosophy---eg., Aristotle and the Romans---but contemporary philosophy has disowned rhetoric in the name of science. It divorced persuasion from truth.

However, if you read the Roman philosophers who were also senators in the Roman Republic (such as Cicero) or political advisors to Roman emperors (such as Seneca)you would quickly find that they argue that rhetoric can only persuade if it retains it's connection to truth. Truth needs a bit of embellishment or ornamentation to connect it to the common life and human emotions if it is to persuade.

Propaganda would then be rhetoric divorced from truth. The political word for this in a liberal democracy is spin. Spin is about gaining control of the issues on the public agenda. You want your issues on the agenda, not those of your opponents. Howard got control of the political agenda this week. In the hot house of Canberra the strategy used was all that masculinity stuff. The content does not matter. It is irrelevant. It's control of the agenda that matters.

Looking back at the ponderous academic apparatus of old style academic philosophy from within the chaotic flow of power in the political machine the image that comes to mind is arse fuck. That philosophy fucked you in the arse and the spurs that were used to fuck you produced monsters.

March 11, 2004

Russell and Adorno

The first Philosophy Jammm of the year was held last Tuesday night. Graham Nerlich, who had been Professor of Philosophy at Adelaide University spoke on Bertrand Russell. The talks this year are intended to be on books of the twentieth century and although Graham had nominated a particular text, An Inquiry Into Meaning And Truth, he did not really address this text, choosing instead to talk about Russell’s life. The main reason for this was that, apart from Principia Mathematica, Russell’s writings have been rather ephemeral in character and somewhat unremarkable. So the speaker concentrated on Russell’s life and the nature of the philosophy it embodied. This largely took the form of a comparison with Socrates. Socrates described himself as the ‘gadfly of society’. He was a deliberate thorn in the side of the state. Like Socrates, Russell saw philosophy as spoken and conversational, rather than written and discursive. The idea of a professional philosopher was an anathema to Socrates. One reason advanced for the ephemeral nature of much of Russell’s writing was that his principal concern was to communicate with ordinary people, rather than specialists.

I walked back to my car with Suzie after the meeting and we talked about being a writer. In had been remarked in the talk that Russell was a prolific writer, producing five thousand words a day. He won the Nobel Prize for literature in the early fifties. We decided that writing had nothing to do with success in publishing or reaching a public. It didn’t matter whether you won a Nobel Prize or no one ever heard of you. A writer is someone who writes, not just occasionally but as a routine day-to-day practice. It’s a way of life and not a measure of some literary success. Most writers aren’t successful in that sense. Whether or not he was successful philosophically, you’d have to say that Russell was a writer who was successful.

One of Australia’s great literature teachers, who before her death taught at the Australian Military College, wrote of Bertrand Russell in The Music Of Love (p. 149): ‘Bertrand Russell’s The Problems Of Philosophy, especially in the last chapter, gives a purer aesthetic pleasure than most of what passes for literature in the world of the modern novelist.’ She had just previously written, ‘For my own part I shall happily go on getting more pleasure from more works of non-fiction than from most modern novels’. Russell gave her that literary pleasure.

I got out my copy of The Problems Of Philosophy. It’s yellowed. It was printed in 1974. But before you start thinking that perhaps I’ve had all this cultural baggage for yonks, let me say this: I bought my copy of Russell’s book in about 1975 but I never read it all. In fact, I have probably read very little of it, and what I did read I probably didn’t read properly. Russell didn’t have a high status in philosophy when I was studying, so being a good little student I didn’t have a very high opinion of him either. The Problems Of Philosophy probably had nice white pages when I last opened it. And if it wasn’t for Graham Nerlich’s talk and Dorothy Green’s remarks I mightn’t have opened it again to find out how yellow it had become. Some books have to wait years for you to read them but books are very patient things.

The last chapter of The Problems Of Philosophy does contain some very pleasant prose. Here’s an example:

‘The free intellect will see as God might see, without a here and now, without hopes and fears, without the trammels of customary beliefs and traditional prejudices, calmly, dispassionately, in the sole exclusive desire for knowledge – knowledge as impersonal, as purely comtemplative as it is possible for man to gain.’ (p. 93)

I was just talking to Wayne about this sentence. He thought that Rosenstock-Huessy wouldn’t like it but we were on the phone and I didn’t get the chance to follow it up. Other things took precedence, and then a locksmith I’d been expecting showed up. Perhaps Rosenstock-Huessy wouldn’t have liked the calmness of Russell’s vision of a free intellect. You may find it hard to believe but I’m not too calm myself when it comes to philosophical discussions. Ask any of the guys. I get a bit passionate about it.

Anyway, I won’t rave on. Just let me say this: another brief look at The Problems Of Philosophy has made it quite clear that Russell is completely hogtied by his peculiarly British philosophical baggage. The penultimate chapter makes it perfectly clear that he hasn’t got the slightest idea what’s going on in Hegel. It’s strange because, as Graham pointed out, he began his philosophical life as a student of McTaggart, who was one of the leading English neo-Hegelians, but they had the strangest ideas about Hegel as well. Perhaps I can induce Gary to say something about the English neo-Hegelians. He knows more about them than I do.

Back to the baggage: the idea of epistemology as first philosophy reigns supreme. Graham didn’t mention that this wasn’t the case with the ancient Greeks, that it is something that creeps in at about the time of Descartes. There is also a notion of the self as essentially incomplete and seeking completion which is rather like the existentialists. It won’t drag all this out. It’s not the point.

The point is that I think that, hogtied as Russell was, he tried to reach beyond philosophy to say what needs to be said, even if he was unaware that that was what he was doing. Consider the sentence I quoted. It’s the kind of sentence that appealed to Green, I’m sure, a sentence with a noteworthy rhetorical beauty. But why was Russell trying to sell the idea with beauty? Why was he trying to seduce us? Well, his philosophising was useless, confused and misdirected, but he knew where it should lead.

Interestingly, another book that Green much admired is Adorno’s Minima Moralia, a book that seek very much the same goal that Russell is trying to articulate through rhetoric. Here’s the last passage from Minima Moralia:

‘Finale. – The only philosophy which can be responsibly practised in face of despair is the attempt to contemplate all things from the standpoint of redemption. Knowledge has no light but that shed on the world by redemption: all else is reconstruction, mere technique. Perspectives must be fashioned that displace and estrange the world, reveal it to be, with its rifts and crevices, as indigent and distorted as it will appear one day in the messianic light. To gain such perspectives without velleity or violence, entirely from self contact with its objects - this alone is the task of thought. It is the simplest of all things, because consummate negativity, once squarely faced, delineates the mirror-image of its opposite. But it is also the utterly impossible thing, because it presupposes a standpoint removed, even though by a hair's breadth, from the scope of existence, whereas we well know that any possible knowledge must not only be first wrested from what is, if it shall hold good, but is also marked, for this very reason, by the same distortion and indigence which it seeks to escape. The more passionately thought denies its conditionality for the sake of the unconditional, the more unconsciously, and so calamitously, it is delivered up to the world. Even its own impossibility it must at last comprehend for the sake of the possible. But beside the demand thus placed on thought, the question of the reality or unreality of redemption itself hardly matters.’ (p. 247)

March 10, 2004

Bataille On Nietzsche#16

In chapter VII of the second part On Nietzsche Bataille turns away from the dialectic of desire inner experience and the risk of connecting with others in which desire leads to erotic and criminal situations.

He turns to Christian ecstasy.The connection?

"Christian mystics crucify Christ. The mystics love requires God to risk himself, to shriek out his despair on the cross. The basic crime associated with saints is erotic, related to the transports and tortured fevers that produce a burning love in the solitude of monastries and convents."

Bataille says that the extreme laceration at the foot of the cross can be compared to non-Christian mystical states.

"For both, sexual desire awakens ecstatic becomes the individual's annihilation. Sometimes the nothingness connected to mystical states is the nothingness of the subject..."

The nothingness is the night of anguish.

March 09, 2004

Art and Propaganda

Gary is away in Canberra so it’s up to me to keep the punters interested this week. I thought I’d take up the issue raised by Gary in his last contribution and to which I replied in a rather knee-jerk way yesterday.

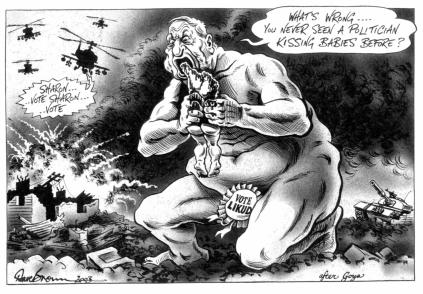

Here’s the cartoon that caused all the kafuffle:

Dave Brown

It is by Dave Brown and it doesn’t paint Sharon and Likud in a very good light. You have to extrapolate from there if you want to see it also painting Israelis or Jews in a bad light. Lots of people don’t like Brown’s cartoon, almost all of Gary’s respondents anyway. I could go on analysing it but I don’t want to upset the troops any more than they’re already upset so I won’t, although I will make some brief points in concluding.

I’ll begin by saying some things about art and propaganda. I’m with Adorno on art. Art is a windowless monad. The idea of a monad comes from Leibniz via Benjamin. In the Trauerspiel book (p. 47) Benjamin writes of an idea as ‘an indistinct abbreviation of the rest of the world of ideas, just as, according to Liebniz’s Discourse on Metaphysics (1686), every single monad contains, in an indistinct way, all the others. The idea is a monad – the pre-established representation of phenomena resides within it, as in their objective interpretation.’

If I use Klossowski’s ideas, which I’ve already discussed (14 January, Klossowski on Art), it might help to clarify the idea of a monad. Klossowski said that artworks were simulacra, the expression of some instinctual obsession and intersubjectively meaningless. The code of everyday signs is made up of simulacra that have become detached from their instinctual basis. Elements of the code that take on a symbolic function have become stereotypes. In works of art the instinctual obsessions are expressed through the vehicle of stereotypes, which is why they seem to be intersubjectively communicable. They’re not just meaningless splashes of colour and unrecognisable form. Indeed, they are very specific. The stereotypes of the nineteenth century weren't much use in the art of the twentieth century. Artworks can be seen as a consequence of the struggle between the instincts and the specific stereotypes of an era. It is in this sense that, to quote Benjamin again, ‘every idea contains an image of the world’ (p. 48).

What Adorno added to this was the notion that artworks, at least the modernist ones, do not look out at this world. They are not models of society because they comment on, say, the current Israeli situation. Rather, they are inward-looking, concerned with form, with the tradition to that point, and this is the source of the struggle between the instincts and the stereotypes.

The dialectic of art is an internal dialectic in this sense, but its products, that is the artworks themselves, are representations of the world out there, including all the blood and guts stuff. That is why artworks are windowless monads. They don’t look through the window because there isn’t one, and so unlike Dave Brown the artist never sees a window of opportunity – it’s a horrible phrase and I am ashamed to use it because of its fascist-speak connotations but it makes the point.

To all you supporters of Zion out there who think that Dave Brown’s cartoon is propaganda I’ll say this: you are completely right. It’s not art, even if it is well-drawn, or powerful, or deeply offensive, or all three. The point is, these are all properties of artworks and other things. Cartoons are other things. In fact, they are propaganda. Gary wrote that cartoons like this ‘show just how powerful images are in political argument’. They shouldn’t be. It all goes to show the low standard of political argument. In fact, I don’t think they have arguments in politics in any real sense. The thing that’s keeping Gary from contributing to Philosophical Conversations is a circus, or better, a theatre but not a forum of debate. Where does this leave the powerful and offensive cartoons? It’s a good question.

Dave Brown’s image is like Goebbels’ images, as one of Gary’s respondents has claimed, but it is also like John Heartfield’s anti-Nazi images of the 1920s and thirties. Truth is not a criterion here. Goebbels might have accurately portrayed some Jew doing something reprehensible but that is not the point. Unlike the art image, whether true or false, the propaganda image aims to persuade. Propaganda is about persuasion and art is about truth, and never the two shall meet, whether it’s Heartfield, Goebbels or Brown who is trying to be persuasive.

One more point: Brown’s image is of Likud, Goebbels’ is of ‘the Jew’, Heartfield’s are of ‘the Nazi’. There is as little reason for considering Brown anti-Semitic on this score as there is for considering Heartfield anti-German. Brown’s propaganda is anti-Likud propaganda, just as Heartfield’s was anti-Nazi propaganda – let’s call it by its proper name. Lots of Likud’s supporters aren’t Jews and lots of Jews aren’t Likud supporters. Someone should point this out to George F. Will. An anti-Semite is someone who aims to persuade others to turn against Jews and Muslims. Brown’s aim is to get people to turn against Likud.

Is this a good thing or a bad thing. Well, it all depends on the available alternatives. The trouble with the political circus in Israel is the same as the trouble with the political circus in Australia: essentially, we only get to choose between different groups of representatives of corporate interests. In Australia, ‘ATSIC’ is an acronym for ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Commission’ although an Aborigine I once met in Melbourne told me that it really stood for ‘Aborigines talking bullshit in Canberra’. Perhaps it’s time to broaden the scope of the acronym to mean ‘Australians talking bullshit in Canberra’. The problem is not just Likud. The problem is corporatism in the public sphere, and corporatism in the public sphere is fascism.

March 08, 2004

anti-Semitism and criticism

Gary, I’m sorry to see that you were subject to a tirade of vitriolic abuse and misrepresentation for republishing cartoons on Sharon and Blair but it is not surprising, for what is taking place at the moment is a propaganda war of massive proportions to back up the violence on the ground. There’s a lot at stake – everything, you could say. But more than this, the tirade is another example of the attack on social criticism of any kind, on which I have been reflecting in relation to my reading group on The Star Of Redemption. It’s the post-modern age, the corporate age, the age where fascism has become wizened to keeps out of sight, if I may paraphrase Benjamin, the age where fascism is next to godliness.

Post-modernism – and by that I mean Foucault, Deleuze, Derrida, Lyotard, Baudrillard, and those gathered around them – is at its very core a rejection of criticism. There are people like Ivan, who have made Foucault’s ideas into a critical theory, but he was immediately attacked and excluded for his trouble. The part of his thesis to attract the greatest ire is his augmentation of Foucauldian ideas with some insights drawn from the early Marcuse (a great Jew). In short, he argued that while the nineteenth century political administration is characterisable in terms of liberal governmentality, the twentieth century represents a different model, what he calls ‘fascist governmentality’. Interestingly, this is about the only chapter of his thesis he has so far failed to get published. I wonder why.

Deleuze and Derrida provide convenient examples of this rejection of negativity but it applies equally to any of the other French writers I just mentioned. In each of these two cases, the goal is to find a way around Hegel’s identity thesis. I’ll put this very crudely and hopefully very simply: the basic idea is that, through negativity, solely through criticism a point will be reached where the process reverses itself and becomes a positive statement – ‘the world is x,’ where x is an idea that no longer encounters nature as resistance. This is the absolute idea, the idea that actually conquers nature and it’s reached without making any prior positive claims. The goal of idealism is reached: I now know the world because it corresponds to my idea. Freedom and necessity are finally reconciled. Adorno is just one, although perhaps the most famous (and Jewish), to point out that negativity can never be anything other than what it is. He thus rejects identity. On the other hand, Deleuze and Derrida try to find a way around this impasse through a positive act of will, as if identity can be achieved just be willing it.

The more positive post-modernists like to think that we’re reached the end of history already. What are Leonard Cohen’s words? (another great Jew) ‘It looks like heaven but it feels like hell. It’s something in between, I guess. It’s closing time.’ How come there’s still resistance if we’ve reached the end of history? Well, the p-ms answer, because after all negativity has been eliminated, a kind of non-negative resistance will continue to exist. You can call it ‘the animal drive’ if you like – it’s the stuff that Bataille talks about. That’s why the end of history seems a fair bit more unpleasant than we might have hoped. It’s just human nature. This smells a lot like a fart to me and it sounds a lot like bullshit. I’m with Cohen, although I still remember what Canetti (yet another great Jew) said about the world remaining young as things go on getting worse and worse, as Dubya calls out, ‘Help me Blair, help me Sharon, help me Howard!’

That great rag of the further-than-far-left, of the get-up-before-dawn-and-flagellate-spartacist-league, the Guardian Weekly – my God! anyone who dares to raise an eyebrow at what’s going on must be a lunatic lefty. Gosh! Golly! What other explanation could there be? Goodness gwatious me! Goodness gwatious, how flirtatious! – published an article by one George F. Will (that’s F. Will, not F. Wit) this week on just the subject of the attack on Gary. According to Mr. F. Will, anti-Semitism is the left’s latest radical chic. He’s got the same view as gary’s detractors. Cartoons are just the thing to express ‘animus against Israel’, just as believing that Israel is a threat to world peace is an example of anti-Semitism, or thinking that the CIA and Mossad organised the September 11 attacks, even ‘a Jewish comedian wearing a Jewish skullcap’ and giving the Nazi salute as ‘Isra-Heil!’ is anti-Semitic, even saying that America is the great Satan is anti-Semitic. People who say they don’t dislike Jews but only Zionists are also anti-Semitic. Although he doesn’t say it, no doubt people who don’t dislike anyone, like Gary, are anti-Semitic because they continue to be negative. That’s all it takes.

I don’t know any of these people so I can’t dislike them but what I dislike in what they do is that they take Judaism away from me. They snatch it away and make it into something I don’t like, something that inspires hatred. But they’re not taking my Judaism. Get your own, you bastards! Sorry. I’m trying to be funny again, just when I ought to be serious. (It must be the left side of the brain that does this. What other explanation can there be?) But seriously, my Judaism is the Judaism of Walter Benjamin, one of the greatest – if not the greatest – intellects of the twentieth century. Benjamin is the only person to come up with a completely different philosophy in the face of the twentieth century, not an abandonment of philosophy such as advocated by the post-modernists, but a completely different philosophy. And before you start, don’t suggest Heidegger or Rosenzweig or the logical positivists, or anybody else. None of them did anything but play with some extant ideas. Hannah Arendt (a greater than great Jew) was right: Adorno is Benjamin’s only disciple.

My Judaism, my Benjaminian Judaism is also the Judaism of those women who have to fill up their supermarket trolleys and then bolt for the door because of the so-called economic reforms in contemporary Israel have driven them into poverty while elite cars become cheaper to buy. In my book, the people who attack Gary are the true anti-Semites, because criticism lies at the very essence of Judaism, for it is forbidden to speak of God but only of the ungodly. Pharisees rule! No thanks.

March 07, 2004

Anti-Semitism.

Trevor,

Alas, I did not get a chance to read your entries other than give them a quick scan. Too exhausted. And I have to catch a plane to Canberra in an hour, check intot he motel, a quick shop at Coles supermarket, a late drink and a catch up of the Sunday papers of the eastern states at a trendy cafe then to bed. It is a 7am start in the political machine.

A quick observation.

I concur with your argument about the easy anti-Semitism that is around the place these days. For an example take a look at the responses in the comment box to an English cartoon I posted over at public opinion on Ariel Sharon and his Likud Party policies. The post was universally condemned as being anti-Semitic and as an expression of Nazism.

Something strange is happening here. Public Opinion got 1500 conservative readers in 24 hours. That (anti-intellectual) conservatism is a strange beast. It colludes with the state in the name of defending the nation from external attack; nasty in tone; deeply cynical; takes the cultural wars seriously; and is full of hate for the old 1968ers.

March 06, 2004

in the belly of the beast

Good to see you writing Trevor. It's sure flowing along. I will read it tomorrow morning over morning coffee if I have time.

I got back to Adelaide from Canberra late Thursday. I was too exhausted to blog then or on Friday. I go back tomorrow night to Canberra for another stint of negotiations.

There is little time to worry about inner experience, or the conflicts involved in reaching out to another individual. One is plugged into a ongoing functionality that is all about power, relationships, communication, mastery and conquest.

Whilst in Canberra I had a lot of dealings with bureaucrats who ran the numbers on the computer models that took a couple of hours to fire up. They sort of gazed across the population as an object. They stood apart from the world they surveyed and manipulated: a spectatorial distance between viewing subject (the bureaucrat) and the viewed object (the health of the population) Theoria was conflated with numbers. Buried in the numbers was a visual metaphor of clarity about numbers that revealed the health of the population. Numbers were everything in the buraucratic gaze.

I kept on thinking of Heidegger. and his idea of the high point of modernity as the conquest of the world as picture. The picture were numbers modelled in mainframe computer since these numbers represented, or corresponded to, the health of the population. The numbers implied that the object stands before us and can be seen with crystalline clarity by the instrumental reason of a Godlike economic science.

Me? I hung onto the lifeworld, the doxa of public opinion, and lived mutilated bodies seeking to avoid the surgeon's knife.

March 04, 2004

More on Benjamin and Celine

I would like to say some things about Benjamin’s criticisms of Céline, now that you have had a chance to read my previous entry.

According to Benjamin, Céline was a popular novelist in a strictly technical sense, representing a form that instead of advancing the proletarian novel was a retreat on the part of bourgeois aesthetics. In fact, it’s actually a Lumpenproletarian form. Like the Lumpenproletariat, argued Benjamin, the form is unable to make visible this defect in its particular subject of history. This is the reason for the ambiguity of Céline’s writing, a writing that portrays the sadness and sterility of a life, its monotony, it’s violence and irrationalism, but not the forces that have shaped these lives. Finally, Céline is unable to say how these déclassés might begin to react against these forces.

Benjamin was at his most Marxist when he wrote this and, as Adorno has remarked, his Marxism was that of someone not from the proletariat who adopted the ideology in a rather programmatic way, as a moral act. He was like most academics and intellectuals who make this move. So I will ignore the nonsense about recognising the class structure of the masses and to exploiting it. In any case, I put the quotation from Adorno’s Prisms in my last instalment in order to discredit the view. There ‘is no real distinction … between town and castle… “State and Party” … They are all déclassés, caught up in the collapse of the organised collective and permitted to survive… [The] burden of guilt is shifted from the sphere of production to the agents of circulation or to those who provide services.’ It is not the job of a writer to exploit the situation for revolutionary or any other purposes. Benjamin knew that. His criticism was quick and cheap.

He is however right that the popular novel is a retreat on the part of bourgeois aesthetics. Indeed, it is hardly a novel at all. One of the reasons for the monotony of Céline’s books is that they make up a kind of fictionalised autobiography, with confessions, reflections and a bit of theorising thrown in. In fact, as a form, Céline’s writing is much closer to Benjamin’s than perhaps the latter cared to recognise.

The retreat on the part of bourgeois aesthetics is part of the retreat of the bourgeoisie, but it’s hard to say whether this is a good thing or a bad thing. I’m inclined to the latter alternative. The fascist (= corporate) society of the present still uses the ideology of the bourgeoisie for its own ends but I think Adorno is right – we are all déclassés. Many of us have become bourgeois in terms of our relations to the means of production – corporate practices have forced increasing numbers of ordinary people into the share market – but we haven’t become the beneficiaries of any new-found wealth. We’ve remained the cringing creeps Adorno described.

I don’t think the form is as mute as Benjamin thought. Read Bukowski. It doesn’t have all the answers but you’ll get a strong sense of who did what and how and with which and to whom. All right, the grand exploiters aren’t standing there behind the brutes, but the current exploitation isn’t carried out by a group of individuals, so there’s no one to expose. Dubya is one of us so there’s no use pointing the finger at him, for instance, or his ventriloquist master (I wouldn’t like to spend my life with Dick Chaney’s finger up my arse). But back to my point: what’s happening is structural and its political.

What do I mean by the last point? Well, I don’t see corporatism as part of the organic evolution of capital. It came about at a point when the organic evolution of capital looked to have reached its end stage and political action was necessary. At the end stage came the end game. Hey, this is reality tv in a big way.

I think Benjamin was right about the observation of nihilism in the popular novel, but I agree with Nietzsche, and Diederich Bonhoeffer for that matter. Nihilism is the sensibility of the twentieth century – what someone like Kracauer would have described as the historical condition of the objective spirit. It’s a curse but it’s our curse and we really have no choice but to run with it. But now, we are getting close to Benjamin’s – and Adorno’s – own position. According to the latter (see Negative Dialectics), the theological task can only be carried on by those who no longer believe in theology.

March 02, 2004

History and Declasse Consciousness

Following yesterday’s entry, I have organised some more material on Céline, material that may lead you to think that the people with whom I argue about Céline are right and I am wrong. If that’s how it comes out so be it. Make up your own mind.

Benjamin only read Voyage To The End Of The Night. Scholem had wanted him to read Bagatelles For A Massacre. Perhaps he did, but if he did he kept quiet about it. All that is available by Benjamin on Céline is a handful of remarks recorded in correspondence or by friends, and an essay in which Voyage is discussed. Benjamin’s verdict on the book was that it reflected the perspective of the Lumpenproletariat, a social group lacking in what Benjamin called ‘class consciousness’. ‘Céline, in his description of it, is quite unable to make visible this defect in his subject.’ The book is a ‘retreat on the part of bourgeois aesthetics’ that nevertheless ‘succeeds in vividly portraying the sadness and sterility of a life in which the distinctions between workday and holiday, sex and love, war and peace, town and country have been obliterated. But he is quite incapable of showing us the forces that have shaped the lives of these outcasts. Even less is he able to convey how these people might begin to react against these forces.’

Scholem, with whom Benjamin discussed Bagatelles pour un massacre had his own views on Céline. He wrote that ‘The book caused quite a stir. That Céline’s nihilism had now found a natural object in the Jews was bound to give one food for thought. Benjamin had not yet read the book, but he was under no illusions about the dimensions of anti-Semitism in France. He told me that those of Céline’s admirers who were influential on the literary scene got around taking a clear stand on the book with this explanation: … it really was nothing but a joke. I tried to show him how frivolous such a recourse to an irresponsible phrase was. Benjamin said this own experience had convinced him that latent anti-Semitism was very widespread even among the leftist intelligentsia and that very few non-Jews … were … constitutionally free from it.’ (Walter Benjamin: Story Of A Friendship, p. 212.)

There is a remark by Benjamin on Céline in the Arcades Project (p. 300) –‘Gauloiserie in Baudelaire: “To organise a grand conspiracy for the extermination of the Jewish race./ The Jews who are librarians and bear witness to the Redemption”… Céline has continued along these lines. (cheerful assassins!)’

In a letter to Max Horkheimer on April 16, 1938, Benjamin wrote, ‘You may have seen Gide’s dispute with Céline… “If one were forced to see in Bagatelles pour un massacre anything other than a game, it would be impossible to excuse Céline, in spite of all his genius, for stirring up banal passions with such cynicism and frivolous impertinence”… The word banal speaks for itself. As you will recall, I was also struck by Céline’s lack of seriousness. Gide, being the moralist he is, otherwise pays heed only to the book’s intent and not to its consequences. Or, being the Satanist he also is, has he no objections to them?’ (Correspondence, p. 558)

Benjamin describes Céline as a popular novelist (Roman populiste). This form ‘represents not so much an advance for the proletarian novel as a retreat on the part of bourgeois aesthetics… It is no accident that … Journey To The End Of The Night … is concerned with the Lumpenproletariat. Like the Lumpenproletariat, Céline, in his description of it, is quite unable to make visible this defect in his subject. Hence, the monotony in which the plot is veiled is fundamentally ambiguous. He succeeds in vividly portraying the sadness and sterility of a life … But he is quite incapable of showing us the forces that have shaped the lives of these outcasts. Even less is he able to convey how these people might begin to react against these forces. This is why nothing can be more treacherous than the judgment on Céline’s book delivered by Dabit, who is himself a respected representative of the genre. “We are confronted here with a work in which revolt does not proceed from aesthetic or symbolic discussions, and in which what is at issue is not art, culture, or God, but a cry of rage against the conditions of life that human beings can impose on a majority of other human beings.” Bardamu – this is the name of the hero of the novel – “is made of the same stuff as the masses. He is made from their cowardice, their panic-stricken horror, their desires, and their outbursts of violence.” So far so good were it not for the fact that the essence of revolutionary training and experience is to recognise the class structure of the masses and to exploit it.’ (Benjamin Selected Writings, 2, p. 752.)

In a letter to Gershom Scholem (July 2, 1937), whom Benjamin always addressed as Gerhardt, he wrote of ‘the peculiar figure of medical nihilism in literature: Benn, Céline, Jung’. (Correspondence, p. 540). He makes a similar observation in the Arcades Project: And again: ‘On anthropological nihilism, compare… Céline, Benn.’ (p. 402)

There ‘is no real distinction, Kafka writes, between town and castle… “State and Party” – they meet in attics, live in taverns … a band of conspirators installed as the police… They are all déclassés, caught up in the collapse of the organised collective and permitted to survive… [The] burden of guilt is shifted from the sphere of production to the agents of circulation or to those who provide services.’ (Adorno, Prisms, pp. 259-60)

Benjamin sees some kind of causal nexus between Expressionism, Jung, Céline, and the German novelist and physician Alfred Döblin: “I wonder if there isn’t a form of nihilism peculiar to physicians that makes its own miserable rhymes out of the experiences that the doctor has in his anatomy halls and operating rooms, in front of open stomachs and skulls. Philosophy has left this nihilism alone with these experiences for more than a hundred and fifty years (as early as the Enlightenment, La Mettrie stood by it).”’ (chronology, Selected Writings, 3, p. 443)

‘La Mettrie, Julien Offray De (1709-1751), French physician and philosopher… His method of inquiry consisted in moving regularly from the empirical sphere of scientific facts and theories to that of philosophy proper, the latter being regarded … as the logical extension of such branches of knowledge as anatomy, physiology, chemistry, medicine and the like. La Mettrie was perhaps the first “medical” philosopher in the complete and true sense… La Mettrie … conceived of the problem of happiness … from the perspective of medical ethics, as similar to … the more comprehensive problem of health. Accordingly, he diagnosed the greatest threat to felicity to be “remorse”, a morbid and “unnatural” symptom.’ (The Encyclopedia Of Philosophy, vol. 4, pp. 379-81)

Benjamin may be onto something here. He writes:

‘In Jung’s production there is a belated and particularly emphatic elaboration of one of the elements which, as we can recognise today, were first disclosed in explosive fashion by Expressionism. That element is a specifically clinical nihilism, such as one encounters in the works of Benn, and which has found a camp follower in Céline. This nihilism is born of the shock imparted by the interior of the body to those who treat it. Jung himself traces the heightened interest in psychic life back to Expressionism. He writes: “Art has a way of anticipating future changes in man’s fundamental outlook, and expressionist art has taken this subjective turn well in advance of the more general change.” … In this regard, we should not lose sight of the relations established by Lukács between Expressionism and Fascism.’ (AP, p. 472, modified)

‘Céline … considered that [his] thesis, which was meant to sanction the end of his medical studies, in fact inaugurated his literary career… how pregnant it seems to be with the work to come! … [The] appalling slip that birth is: such is the object of Céline’s thesis… In a maternity hospital in Vienna … two workrooms, two methods. Whereas Bartch uses midwives, Klin only uses students. The result: his department is a slaughterhouse… the conclusion … if expectant mothers run fewer risks when they are handled by midwives, it’s because, unlike students, midwives are forbidden to perform autopsies. “It is the fingers of the students, soiled during recent dissections, that carry the fatal cadaverous particles into the genital organs of the pregnant women”… Woman is in labour, and she is giving birth to death… it is death, and death alone, that ushers us into the heart of the matter.’ (Bonnefis, Céline: Recall Of The Birds, pp. 17-9)

‘Oh, you’ll say, what about the gas? You complain about the gas bills? … just give yourself the gas! … chin up! … read your favourite newspaper … people who can’t take it any more give themselves the gas! … Not so good! After thirty-five years of medical practice I can tell you a thing or two … they don’t always make it … far from it! they get revived … they don’t die but they suffer plenty … on the way out, and on the way back … a thousand deaths, a thousand recoveries! and the smell! … the neighbours come running! … they wreck the joint! if they’ve stolen too much, fire’s the answer! … they set fire to the curtains … a little more suffering for you … asphyxia and burns … to cap the climax … No, gas is bad business … the safest method, take it from me, I’ve been consulted a hundred times, is a hunting rifle in your mouth! stuck in deep! … and bang! … you blow your brains out … one drawback: the mess! … the furniture, the ceiling! brains and blood clots.’ (Céline, Castle To Castle, pp. 31-2)

‘Journey To The End Of The Night … flabbergasted me… The book penetrated my bones, anyway, if not my mind. And I only now understand what I took from Céline and put into the novel I was writing at the time, which was called Slaughterhouse-5. In that book, I felt the need to say this every time a character dies: “So it goes”… It was a clumsy way of saying what Céline managed to imply so much more naturally in everything he wrote, in effect: “Death and suffering can’t matter nearly as much as I think they do. Since they are so common, my taking them so seriously must mean that I am insane. I must try to be saner.”’ (Kurt Vonnegut, introduction to: Céline, Rigadoon, pp. xii-xiii)

March 01, 2004

Reading Celine

I’m still thinking about my reading group four days later. I guess it’s a measure of how little there is in my life. It was my last social event, after all. Here’s what’s bothering me.

Another topic to come up more than once is Céline. I seem to fall out on this topic as well. Whenever Céline comes up in conversation the accusation of anti-Semitism is soon to follow. I say, ‘Céline wasn’t an anti-Semitic. He hated all races equally.’ W. sniggers. She’s heard it before. The thing is, getting too trigger-happy with accusations of anti-Semitism has become a way of stifling conversation. Instead of letting the topic drop, I play the “Bukowski defence”: some guys, like Céline and Hamsun and Pound have just got to take the opposing side to the popular view. There seems to be some agreement with this when it comes to Pound. No one appears to have heard of Hamsun – they should read Hunger then they won’t forget him – and Céline, well, he’s simply beyond the pale. ‘Have you actually read Bagatelles?’ I ask. No one has read it. None of us can read French. Anyway, almost impossible to get hold of is Bagatelles. There’s a reply nonetheless: ‘I’ve read quotations from it. I’ve read enough.’

They’re always read enough – that’s the trouble. I haven’t. I want to read more. I don’t want to pass judgment, not because of some sort of moral stance but because it gets in the way. All reading should be a physiognomy – constructing the writer from his self-portrait in his books. And there’s also something about the prose you can’t ignore. Take the following sample from Guignol’s Band:

‘Boom! Zoom! . . . It’s the big smashup! …The whole street caving in at the water front! ... It’s Orléans crumbling and thunder in the Grand Café! … A table sails by and splits the air! … Marble bird! … spins round, shatters a window to splinters! … A houseful of furniture rocks, spurts from the casements, scatters in a rain of fire! … The proud bridge, twelve arches, staggers, topples smack into the mud. The slime of the river splatters! … mashes, splashes the mob yelling choking overflowing at the parapet! … It's pretty bad…

Our jalopy balks, shivers, squeezed diagonally on the sidewalk between three trucks, drifts, hiccups, it’s dead! Fagged engine! Been warning us since Colombes that she can’t hold out! with a hundred asthmatic wheezes … She was born for normal service … not for a hell-hunt! … The whole mob fuming at our heels because we’re not moving … That we’re a lousy calamity! … That’s an idea! … The two hundred eighteen thousand trucks, tanks and handcarts massed and melted in the horror, straddling one another to get by first, ass over heels, the bridge crumbling, are tangled up, ripping each other, squashing wildly … Only a bicycle gets away and without the handle bar…

Things are bad! … The world’s collapsing!…

“Stop blocking the way you lousy pigs! Go take a crap you slimy lice!”’

That’s page 6, the first page in my copy. The last scene in the second volume of this story (London Bridge) also takes place on a bridge and, as Bonnefis (Recall Of The Birds) points out, bridges are places of great danger in Céline’s books, straddling the abyss, and on the bridge are all the classes of society, or all the déclassés of society, as they actually are, not as they exist in someone’s honey-dripping socialist theory, as they really are. ‘Go take a crap you slimy lice.’ Get out of my way. I don’t want to plunge into the abyss.

If we imagine that Bataille is on the bridge, that he’s been trapped there for months, so long in fact that he’s managed to carve out a little space in the whirlwind where he can crouch and scrape while he waits with the rest of humanity for the eye of the storm, then we begin to get on idea of the circumstances in which the writing of On Nietzsche took place. Céline is focused on the sliding around on the bridge; Bataille is staring over the edge.

Bataille, Sacrifice, van Gogh

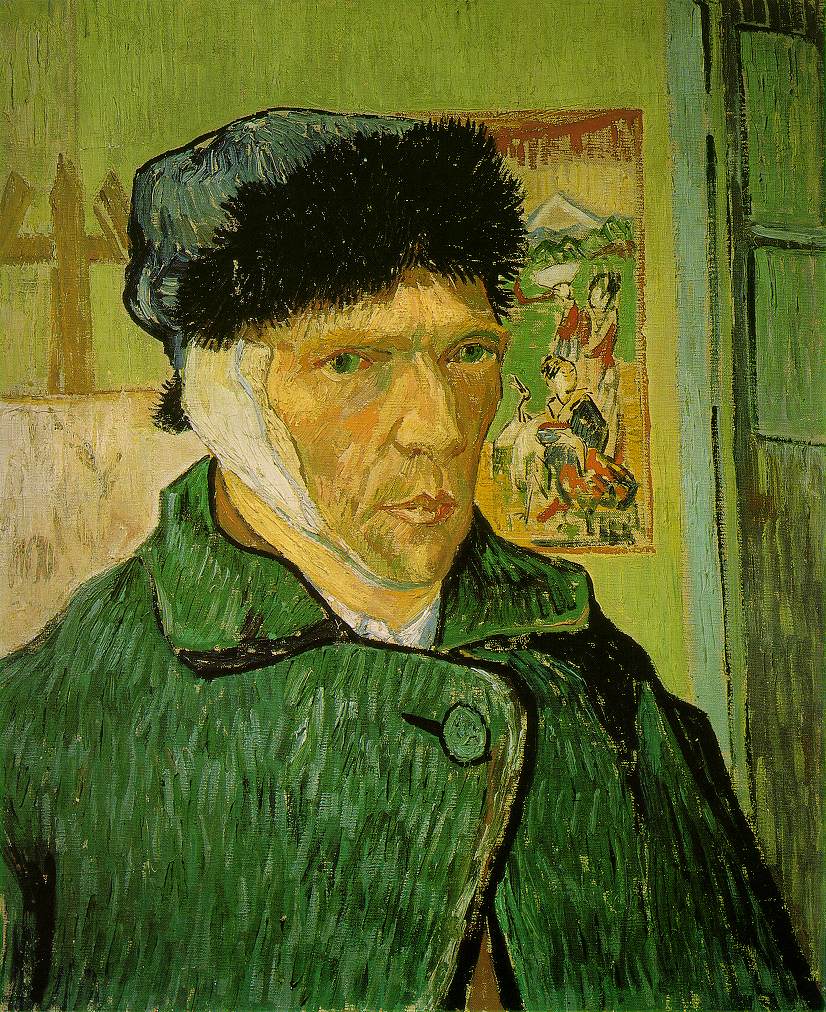

An example of sacrifice. Van Gogh cutting off his left ear.

Van Gogh, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, 1889

This is Bataille from his 'Sacrifical Mutilation and the Severed Ear of Vincent Van Gogh' in Visions of Excess: