February 18, 2004

Wuthering Heights

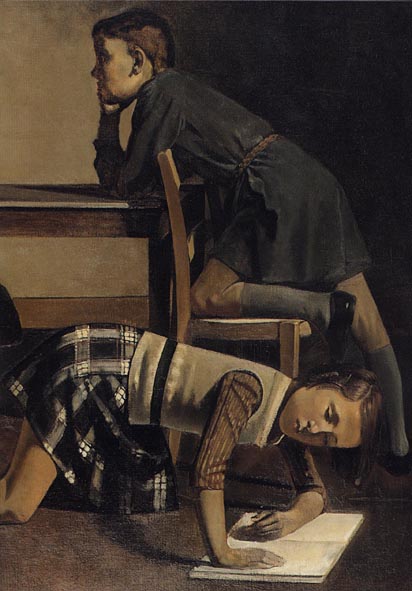

I recently bought a little book called ‘Balthus In His Own Words’ (Balthus In His Own Words: A Conversation With Cristina Carrilo De Albornoz. New York: Assouline, 2001.) I have been long aware of Balthus’s interest in Wuthering Heights, which I have been inclined to see in Bataillean terms. Whether or not this is imposing something on Balthus that is not there I cannot say. In any case, it wasn’t until I’d been through this book that I realised how much Wuthering Heights had been a constitutive interest in his painting. I say ‘been through’ rather than ‘read’ because there is not a lot of text but plenty of illustrations, and it was from the illustrations that I learnt something of the constitutive role that Wuthering Heights played. I’ve collected a few books on Balthus and have seen a pretty good range of his work, but I can recommend this book because of the focus on Balthus’s Wuthering Heights illustrations. There are eight in all, which is more than any other book I have, and they give the reader a good sense of the significance of the book.

Balthus’s paintings are like book illustrations, a characteristic he shares with his brother Pierre. Pierre’s illustrations are largely of his own books. On this point I’d recommend The Decadence Of The Nude (Pierre Klossowski & Maurice Blanchot, London: Black Dog Publishing, 2002 – an excellent book with bilingual text), which has a good range of illustrations from The Baphomet and Roberte ce soir and The Revocation Of The Edict Of Nantes.

In saying that Balthus’s paintings are frequently like book illustrations, I mean that they seem to have a certain narrative quality, as if they illustrate a scene from a story. It is this feature of his work, I might conjecture, that has attracted the attention of a number of writers. I will say some things about these writers another day, particularly the fictional prose of David Brooks and the poetry of Stephen Dobyns.

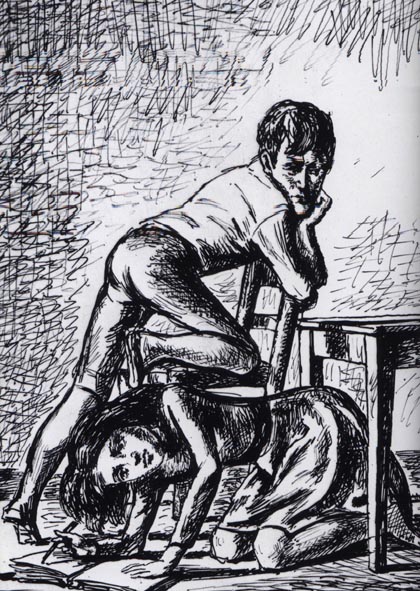

But back to Balthus, his painting, and the general influence of Wuthering Heights. As the above illustrations show, an illustration of a scene from Emily Brontë’s book becomes a painting on an unrelated theme in Balthus’s hands. For me, it is not merely that a scene from the book might become another unspecified scene that perhaps isn’t from any book at all, although this possible feature is interesting in itself. Somehow, the mood, the atmosphere of Wuthering Heights, which Balthus captures so brilliantly, infects his painting as a whole. Let me draw a long bow and say that perhaps this atmosphere of Wuthering Heights, dark and brooding, childish and sinister, perhaps even evil, pervades all of Balthus’s painting. It’s a lot to get from one little book but that’s my experience, for what it is worth.

What does Balthus himself have to say about Wuthering Heights? In this book, not a lot, but what he does say is quite interesting – although I hope it doesn’t provoke an outbreak of Freudianism. He says:

‘I am a very emotional man, perhaps too much so… My youth was an absolute whirlwind of Feelings, exactly like Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, which I illustrated. I was completely at home in this novel. It described my youth perfectly. I was in love with Antionette – de Watteville – and I was determined to win her. But Antionette, on top of being a difficult girl, was already engaged to someone else. I reread her letters every evening. I think that, like Heathcliffe, I didn’t want to leave adolescence.’ (p. 14)

Balthus himself has said that it is wrong to attempt to psychoanalyse his paintings, although that didn’t stop the man he said it to from doing precisely that – but more of that anon (meaning: another day). For mine, it is better to look on what Balthus is doing from Karen Blixen’s perspective – that is, it is wrong to try to make a story into life; instead, the artist must make a story out of life. And that is exactly what Balthus is doing, in my book. He is remembering that he is a bit of a Heathcliffe in order to create art. His life provides the raw material. His paintings seem to tell a story because that is exactly what is happening. Elias Canetti got annoyed with the Bible because everything that happened to him was already recorded in there. Perhaps Balthus might have had a similar experience of Wuthering Heights.

Posted by at February 18, 2004 09:39 AM | TrackBack