December 31, 2004

Heidegger v Descartes

I know the image poppy in a computer game (Starwars)sense, but it does captures the idea of confrontation:

It suggests that the history of philosophy is a battlefield with reasoning being used as a weapon.I like it, even though the image downplays the importance of a dialogue between the French and the Germans. I prefer that conception tothe Wittgenstein view tht philosophy is "a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language."

Starwars. That series was all about technology and mysticism.

Could we not have a dialogue about technology, machine metaphysics and a technological mode of being. A dialogue conducted from the perspective of the biomedical future of human beings, human genetics and biopsychological engineering.

That would enable us to trangress the current debates about our bio-futures currently conducted by American liberals.

December 30, 2004

heavy comment spam=upgrade

Due to very heavy spamming over Xmas the file mt-comments.cgi has been disabled. So the comments function is turned off. No comments can be made. The trackback function is turned off as well.

Silence. Tis odd. I've become so used to the waves of comment spam washing over the weblogs.

It was the end of the road for the old style free Moveable Type publishing system.The philosophical conversation in the commons is killed off by comment spam. 800 on this site in a couple of hours from a spambot. Some weblogs have been getting 10,000 an hour! Comment spam is a conversation killer.

We are currently in the process of a long overdue upgrade to Movable Type v3.14 plus MT-blacklist as a first step to deal with the pernicious comment spam problem. It would appear that there has been a targeting of MT by the spammers.

This is due to the popularity of its publishing system and Movable Type's susceptiblity because it is designed for very open commenting.Movable Type's built-in comments functionality did not require registration and it allowed bloggers to block comments only by IP address: a restriction spammers can easily avoid. Hence a spam bot could, and did, enter hundreds of unwanted spams in a matter of minutes into the comments of a largely unprotected weblog.

I've been waiting for the new style Movable Type to fix the bugs in their MT-blacklist software that resulted in escalating comment spam, which in turn caused extreme server loads. Movable Type has been working on the problem.

Now I'm not sure whether the spam comment problem has been solved. People are voting with their feet and moving on: onto WordPress. As there is no silver bullet to remove comment spam I've decided to stick with a now corporatised Movable Type.

That means paying for a more sophisticated publishing system (fee based licence system) and using the specially designed plugin architecture. I'm happy to do that.

In the meantime--until the upgrade has gone through--comments can be emailed to me and I will incorporate them into the post as an update.

Update

The Movable Type upgrade has been successful. However, problems have been encountered with installing the MT-Blacklist plugin.It is far too far complex for me. I've called in help from my local tech support. We will work on it tomorrow.

Jay Allen writes in response to my comment that "People are voting with their feet and moving on: onto WordPress." He replies:

"Not as many as you might think...After you upgrade everything (which will help immensely) you may want to also install Brad Choate's MT-DSBL. I installed it last night and so far not a single spam has even gotten TO MT-Blacklist to be blocked or moderated. It's eerie quiet...If you're having problems, go search on the MT-Blacklist forums for an answer. It's probably already been written about. See forum."

Thanks Jay.We will most certainly follow your advice re Brad Choate's MT-DSBL and the MT-Blacklist forums. But first the installation itself.

Update:31 Dec.

Installing the MT-Blacklist plugin is very complex. We are struggling with it.This is no easy task--it is beyond the capabilities of ordinary bloggers such as myself.

I reckon that essential plugins such as MT-Blacklist should be really be part of Movable Type 3.14 itself, not an add on extra. There are 7 pages of instructions. It is a major job---it is a job for the professionals.

Very hot weather and New Years eve is not the right time to be doing this kind of work. We will have another crack at it tomorrow.

December 29, 2004

primacy of the practical

For some reason I could not post this comment at this earlier post on Heidegger and Aristotle. I suspect that comments have been turned off due to a massive comment spam attack yesterday--over 1100 with 800 on this weblog alone.

The comments are in italics and, with more room, I've expanded the line of reasoning.

"Aristotle's practical ethical philosophy, which is concerned with a flourishing life well lived, promises a way to opt out of complete systematicity, without embracing romanticism, aesthetics and celebrating the non-conceptual and the subjectivity of inner experience. It opens up a return to the concrete.Pointing to the idea of ethical life also provides a way to counter the dominant "postmodern" trend in “Continental Philosophy” which casts a stuffy Hegel, a unified Platonist notion of closed, rigorous, totalizing reason, and closure of the Hegelian dialectic, under suspicion in favor of a radical Nietzschean critique that opens the door to the thematics of difference.

Ethical life provides a different way to link theoretical and practical reason."

A lot of French philosophy that reacted against their construction of Hegel, the closed Hegelian circle, and theoretical reason of science getting the truth about the fundamental furniture of the world is dominated by aesthetic concerns, rather than ethical ones.

What we get on the aesthetic reading of the conceptual is a play around what is left over: variously the “night” that remains after the closure of the Hegelian dialectic; a return to nothingness; a presencing of absence, a murmuring silence, the void, that which cannot be said et etc.

Once God used to fill the gap of the other. But God is dead. So what is left beyond the categories of reason is the ineffable that has no linguistic status. It is seen as a romantic murmuring silence, non-knowledge, individual experience beyond the social, what is dissolved, as bodily sensations, flushes, and affects.

Often this conception of inner experience (eg., Bataille's mystical states of ecstasy and rapture or Klossowski's unconcious chaotic forces) reminds me of a dialectics in reverse. According to this aesthetic romanticism we face that which we cannot know. This renders as inoperative all attempts at comprehending. It is all about death.

Another way of reading what is remaindered or left over by theoretical reason is to makrk the leftover as practical reason--- what is suggested by Hegel's master-slave dialectic. The focus here is on the active, working body through which human beings act on, and shape, the environment they find themselves within. The categories of this practical reason do not represent reality as truth; rather they construct it in terms of making sense of our life by us as historically situated human beings shaping our world, and being shaped by it. Thinking is involved in the practical transformation of the environment we find ourselves within. Thinking is embodied thought.

The primacy of the practical is what links American pragmatism and Heidegger’s hermeneutic phenomenology. The latter Heidegger does have a conception of our way of living being warped by a technological mode of being that lays waste to nature. His critique of technology has an ethical current, as he is concerned to relate to technology in a way that not only resists its devastation but also gives technology a positive role to play in our lives.

December 27, 2004

Bataille: what's missing

I'm continuing to read the diary section of Bataille's On Nietzsche. He continues to dig away into his subjectivity, into his feelings, beliefs and desires. If we ignore all the God talk about absolutes, celestial glories and the universe, then bits of his reflections about his inner experience do make sense. I can connect with, and understand, some of them, even though I think that mysticism is a temptation to be avoided.

In chapter 5 of the diary Bataille says:

"I hate lies (poetic nonsense). But the desire within us has never lied. There's a sickness in desire that oftern makes us perceive some gap between the object imagined and the real object. It's true, the beloved individual differs from the conception I have of that individual. What's worse: to identify the real wth the object of desire it seems, presupposes extraordinary luck." (p.69)

It seems to similar to what psychoanalysis means by projection: a cutting off what the super-ego perceives as "bad" aspects of oneself (e.g. weakness or aggression) and projecting them onto someone else "over there" where they can be condemned, punished, etc. It is associated with, and constructed in part by, the repression of that which is too painful to remain in consciousness. It is this kind of unconscious projection that determines our behavior, especially in personal relationships.

Bataille does not seem to have any sense of philosophy as a healing art that tries to cure us of the beliefs and desires that make us sick and cause us to live such miserable lives. It is the gap between the object imagined or projected and the real object as the individual human being makes us miserable. If we are being judged in terms of the good projection we are always seen to be inferior; if we are judged by the bad projectionwe are seen negatively, and so need to be punished and attacked as threatening.

This diary is more than romantic self-expression. Being the good Catholic Bataille abolishes the tormenting absence of his lover until he can possess her under his roof. He accepts that carnal love involves excesses of suffering, and accepts the bitterness, anguish and torment, knowing that he only reach his love in a few moments of chance. The excess is what makes him alive. He wants to experience the pain. It seems that he accepts that we are castrated, lacking, lacerated and split anway. So lets up the pain.

Another way of reading this is that Bataille is being made sick by the poisons inside him. Bataille is a soul in distress entrapped in torment. His suffering body needs healing byremoving some of the poisonous projections and tormenting desires. But Bataille turns away from the therapy offered by psychoanalysis to intensifyhis own torment.

Though he has moved beyond the traditional Catholic disgust with his bodily desires Bataille remains trapped in his obsessions of love. For Bataille personal erotic love has come to replace religion as bearing the weight for his longings for transcendence, for mysterious union. All that desire and passion flows to the heavens into the sacred. In this religion of love we have obsession, madness, attempted escape and death. Yet Bataille sees no need for therapy: no need to expose the myths and delusions that prevent us from relating to one another in less destructive ways.

He welcomes the pain. The writing is about pain. He loads up the pain. Just like a good mediaeval Christian mystic.

What do we make of this lack of desiring to get well? Bataille is sick so why does he not want to get well?

I recoil from Bataille, as he has no desire to heal himself. I distrust the violence. Is the "ecstatic anguish," more a form of masochism?

Bataille does whip up the intensity of the emotional pain, just like a mystic. I read this as a perverted Catholic impulse toward sacrifice, ritual and excess. But the violence overflows the limits of mysticism.

Bataille is writing pain. So argues Amy Hollywood in her Sensible Ecstasy: Mysticism, Sexual Difference, and the Demands of History. Writing pain is Bataille's response to history. Meditation on pain is a way of dissolving subjectivity by inducing a constructed traumatic experience.

Hollywood argues that in this response to history Bataille's texts become 'operations' of ecstasy; they continually erect and overturn distinctions between 'experience' and 'theory,' 'subjective' and 'objective,' 'inner' and 'outer.' The writing of the text is an erotic, mystical, religious exercise; a writing based on a conception of mystical speech that assumes the ultimate futility of language and embraces absence and paradox in the place of meaning.

Why the desire to dissolve subjectivity? As a way of moving beyond the scientistic Enlightenment's dualism? So why the violence? Why value suffering in such an intense excessive form that one sails dangerously close to the line that signifies the serial killer?

December 24, 2004

Bataille's diary: mysticism & sex

I've started reading Part 111 of Bataille's On Nietzsche, which is more or less a diary he kept in the early part of 1944. I guess the experience of reading this text (and Klossowski's Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle) embodys a lived process of thought by myself as gripped by, exploring, and trying to work through, the contrary tendencies and shifting moods. It is a new way of reading a text.

The question I keep asking myself is: Why was Christian mysticism so attractive to alienated secular French intellectuals in the 1930s? I have no answer beyond interpreting it as part of a radical critique of the anti-bodily, anti-emotional character of the Enlightenment. They had the hyper-rational conception of what it means to be human and live in the world--presumably Descartes rather than the materialist's conception of humans as a machine?

The enlightenment in our era has perverted itself by overrationalization and mechanization. Bataille was alert to such dangers. But why his turn to mysticism?

With that in mind I go back to reading Bataille's diary section of On Nietzsche. In Chapter 111 he writes:

"My obsessive need to make love opens on death like a window on a courtyard.To the extent that lovemaking calls up death (like the comical ripping apart of a painted stage set) it has the power to pull the clouds from the sky." (p. 61)

Death means both a release from the burden of meaning and a dissolving into a void. It is a going beyond what is; a transgression of everyday life. At the height of desire, one is haunted by death.

Does the desire for one another actually masks a desire for death? I have no idea.

Sex, violence and death. Where are the boundaries between them?

Presumably the sex-death boundary is more social than natural and it is maintained through our signifying practices in everyday life. For Bataille the sociologist/anthropologist taboos are the structures which protect societyfrom inherent contradiction. They establish the core identity of the culture by establishing precisely what must be abjected. Transgression is then the means by which the desires and frustrations masked, or set up, by taboo are released in socially-sanctioned ways.

Bataille, as the individual writing On Nietzsche, is trying to release the desires and frustrations masked by established Christian religion. He trusts the unconscious desires and distrusts the social masking. The focus is on the violent intensity of the desires not on the need to heal the damage the masking has done. So what connects desire and death?

Love decays and this decay reminds me of my own movement toward death? I don't buy it for a moment. Life decays from within? Hardly. Unconscious desire is always attached to death--a promise of release from the demands of consciousness leads to death? Perhaps.

But the interlinking between desire and death for Bataille has more to do with Christianity.Christianity has an obsession with death, loss and failure. A core tenet of Christianity is that man through desire (Adam) brought death (Christ) into the world. Consequently, death must haunt desire as the source of all suffering.That is more like Bataille.

I come back to question above: Why was Christian mysticism so attractive to alienated, secular French intellectuals in the 1930s?

From what I can make out, Bataille is writing through visions and physical feeling. This is not the mysticism as an acceptable form of religion that is based on an intellectual mystical union. It is the more bodily, experiential and visionary form of mysticism that Bataille is expressing; he is articulating a subjectivity deeply grounded in bodily life. The sacred can only be known through intense pain and deep emotional ecstasy.

Bataille accepts that our emotional life is a valuable source of experience and provides crucial kinds of knowledge. He tries to engender it. Is Bataille seeking to revitalize contemporary Catholicism by recovering untapped aspects of Christian mystic thought?

Sartre interpreted Bataille's mysticism as an escapism, as a rejection of history and its ethical and political imperatives. Maybe Bataille is using a bodily mysticism to engage with history and temporality differently, through subverting a series of binary oppositions entrenched in the rationalistic Enlightenment tradition?

December 23, 2004

Justine et Juliette

Hi Gary,

You write in a previous entry:

You write in a previous entry:

So those who deny their darker desires and natures and try to be moral and virtuous are the ones most likely to behave badly, while the people who are socially condemned as immoral because they give free expresion to their dark desires who often display true virtue. The former live their lives within a rigid moralism and behavioral codes and have a supercilious social pretense. These paragons of society -- the priests and moral straightners -- act behind the facade of their pious sanctity to perform the cruelest, most despicable acts, sexual and otherwise.

That is de Sade is it not? Justine, suffers for her virtue, while her sister Juliette profits through debauchery. Justine is punished for her virtues - chastity, piety, charity, compassion, prudence, the refusal to do evil, and the love of goodness and truth.

I find the relation between Justine and Juliette in Sade's texts really interesting, but perhaps not as oppositional as it might seem. In keeping with your description of Sade as a radical materialist, there's a sense in which Juliette is simply more realistic, or more in tune with nature, and her own nature, than Justine. Reading Justine, I found it very frustrating that she seemed simply incapable of learning a lesson: certainly that her morals were so incorruptible (or inflexible)—but also that time and again she had to reveal the entire story of her pathetic life to her next "maître", as if he were her confessor. It seemed to me that in this way Sade rendered her complicit in her own victimisation; perhaps like a masochist, deriving pleasure from the cruelty inflicted upon her, but unconsciously (or dishonestly). The difference is that Juliette does so honestly.

Maurice Blanchot, in his essay Sade, which appears at the beginning of my copy of Justine, Philosophy in the Bedroom, and Other Writings (Grove Press), suggests that Justine and Juliette each present a different response to the same circumstance:

...the two sisters' stories are basically identical, ... everything which happens to Justine also happens to Juliette, ... both go through the same gantlet of experiences and are put to the same painful tests. Juliette is also cast into prison, roundly flogged, sentenced to the rack, endlessly tortured. Hers is a hidwous existence, but here is the rub: from these ills, these agonies, she derives pleasure; these tortures delight her... those uncommon tortures whihc are so terrible for Justine... for Juliette are a source of delight... Thus it is true that Virtue is the source of man's unhappiness, not because it exposes him to painful or unfortunate circumstances but because, if Virtue were eliminated, what was once painful then becomes pleasurable, and torments become voluptuous. (pp.49 - 50)Juliette is not outside the sphere of suffering—nor is she a stoic—but rather, she embraces and enjoys suffering by taking the other's perspective upon it (like the Greek whom Nietzsche exhalts for being able to view hardship from the eyes of the gods, with tragedy). She is in this sense a sovereign individual who (again in Blanchot's words) "is able to transform everything disagreeable into something likable, everything repugnant into something attractive" (50). In this way, she is truly an artist.

December 22, 2004

Heidegger & Aristotle#2

What we can say about Heidegger and Aristotle in a sentence?

Why a sentence? It is late, very hot, and I'm tired, too tired to work with Stuart Eldren's academic text. What is more it is getting close to Xmas and that means the odd drink or two. In the heat a drink means knockout. That means falling asleep at the keyboard trying to concentrate reading a tough academic text online.

So here is a stab at a sentence before I fall asleep.

Though Heidegger recovered a practical reason in Aristotle's texts he foregrounds the ontological dimension, downplays the ethical, and forgets about the link between the ethical and the political.

Oh,I can add a bit more. An inference.

The ethical is buried. It-- the practical concern to live well-- is what needs to be recovered.

Is that one sentence a reasonable account of Heidegger's engagement with Aristotle?

Update

The primacy of the practical is what links Aristotle, American pragmatism (Dewey), Heidegger's hermeneutic phenomenology and environmental philosophy. Practical philosophy was what Gadamer highlighted in his intepretation of Heidegger.

There is more on this connection between American pragmatism and Heidegger by Ali Rizvi over at Habermas Reflections. Ali explores the links from the perspective of Habermas, the recoil from the spectator model of knowledge based on the passivity of sense experience, and the shift to understanding of knowledge based on action or practice.

Instead of reading Aristotle through Heidegger so to recover Aristotle's practical philosophy, we can we re-read Heidegger through the lens of Aristotle to make with, and recover, an ethical knowledge and inquiry. What we make contact with is a practical ethical philosophy is one concerned with our health and sickness, and it aims to help us to live more flourishing lives.

This then allows us to talk in Nietzsche's terms about modes of valuation.

What is missing in Heidegger is a compassionate philosophy that intervenes actively in the world to help ease our suffering from living damaged lives. So we can read Heidegger in terms of this lack.When we do we come across 'care' and 'concern' as modes of being-in-the-world.

December 21, 2004

William Burroughs: Interview

With Trevor having all but disappeared from philosophical conversations the posts on literature have pretty much dried up. That is a pity.

An interview with William Burroughs from the Centre for Book Culture.org courtesy of Matt at pas au-dela The interview was conducted on 4 July 1974, the day before William Burroughs left England for good and went back to live in America. It was conducted by Philippe Mikriammos.

It is many a long year since I've read Burroughs. An online text. I sort of file him away under the beat culture of post-World War II America that foreshadowed the counter culture of the 1960s. My memory is that the romance about being a young man on the road in America that was akin to a rite of passage.

I never really clicked with Burroughs and all the stuff about his own fantasies, obsessions and paranoid imagination. I understood and grasped his suspicions about language and words, even though his life as a writer was defined by language. I had read Naked Lunch" whilst reading banned European and American classics (eg., Henry Miller) in New Zealand when at university. I was searching for something different to the boring middle class novel (bourgeois novel?) with its structure that gave the comfort of secure moral frameworks, recognizable characters, a narrative and a moral criticism of life.

Burroughs has been rediscovered by a younger generation for whom the Beats and hippies that he once inspired are the stuff of movies. I reconnect with Burroughs these days though his experiments with text and music.

PM: To what extent is the prologue to Junky autobiographical?

WB: Largely.

PM: Several people have mentioned a text of yours called Queer, which would be a continuation of your Mexican adventures and of Junky. What has become of these pages?

WB: It's in the archives. Now, the catalogue of the archives was published by the Covent Garden Bookshop. It took us five months to get all the manuscripts, letters, photographs, etc., from fifteen, twenty years. And the archives are in Vaduz, Liechtenstein. Whether they will let it be transferred to Columbia University in America, I don't know. But Roberto Altmann, who has the archives at the present time, has not made them available yet. He is setting up something called the International Center of Arts and Communication in Vaduz. But they had a landslide which destroyed part of the building, and they haven't opened it yet. The catalogue's a very long book; it's over three hundred pages. And I wrote about a hundred pages of introductory material to the different files, and where this was produced and so on and so forth. Literary periods, what I wrote, where, and all that, is in the catalogue, and the material itself, including this manuscript Queer, is in the archives.

PM: Did you use parts of the Queer material in other books?

WB: No, no. Frankly, I consider it a rather amateurish book and I did not want to republish it.

PM: In The Subterraneans, Kerouac spoke of "the accurate images I'd exchanged with Carmody in Mexico." Does this sentence refer to experiences in telepathy and non-verbal communication between you and him?

WB: Well, I think we did some elementary experiments, yes.

PM: Have you been influenced by Celine?

WB: Yes, very much so.

PM: Did you ever meet him?

WB: Yes, I did. Allen and I went out to meet him in Meudon shortly before his death. Well, it was not shortly before, but two or three years before.

PM: Would you agree to say that he was one of the very rare French novelists who wrote in association blocks?

WB: Only in part. I think that he is in a very old tradition, and I myself am in a very old tradition, namely, that of the picaresque novel. People complain that my novels have no plot. Well, a picaresque novel has no plot. It is simply a series of incidents. And that tradition dates back to the Satyricon of Petronius Arbiter, and to one of the very early novels, The Unfortunate Traveler by Thomas Nashe. And I think Celine belongs to this same tradition. But remember that what we call the "novel" is a highly artificial form, which came in the nineteenth century. It's quite as arbitrary as the sonnet. And that form had a beginning, a middle, and an end; it has a plot, and it has this chapter structure where you have one chapter, and then you try to leave the person in a state of suspense, and on to the next chapter, and people are wondering what happened to this person, and so forth. That nineteenth-century construction has become stylized as the novel, and anyone who writes anything different from that is accused of being unintelligible. That form has imposed itself to the present time.

PM: And it's not vanishing.

WB: Well, no, it's not vanishing. All the best-sellers are still old fashioned novels, written precisely in that nineteenth-century format. And films of course are following suit.

PM: Would you say that Kerouac also belonged to the picaresque novel?

WB: I would not place Jack Kerouac in the picaresque tradition since he is dealing often with factual events not sufficiently transformed and exaggerated to be classified as picaresque.

PM: Isn't it a bit striking that a major verbal innovator like you has expressed admiration for writers who are not mainly verbal innovators themselves: Conrad, Genet, Beckett, Eliot?

WB: Well, excuse me, Eliot was quite a verbal innovator. The Waste Land is, in effect, a cut-up, since it's using all these bits- and-pieces of other writers in an associational matrix. Beckett I would say is in some sense a verbal innovator. Of course Genet is classical. Many of the writers I admire are not verbal innovators at all, as you pointed out. Among these I would mention Genet and Conrad; I don't know if you can call Kafka a verbal innovator. I think Celine is, to some extent. Interesting about Celine, I find the same critical misconceptions put forth by critics with regard to his work are put forth to mine: they said it was a chronicle of despair, etc.; I thought it was very funny! I think he is primarily a humorous writer. And a picaresque novel should be very lively and very funny.

PM: What other writers have influenced you or what ones have you liked?

WB: Oh, lots of them: Fitzgerald, some of Hemingway; "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" was a great short story.

PM: Dashiell Hammett?

WB: Well ... yes, I mean it's of course minor, but Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler in that genre, which is a minor genre, and it's not realistic at all. I mean this idea that this is the hard boiled, realistic style is completely mythologic. Raymond Chandler is a writer of myths, of criminal myths, not of reality at all. Nothing to do with reality.

PM: You have developed a personal type of writing called the "routine." What exactly is a routine?

WB: That phrase was really produced by Allen Ginsberg; it simply means a usually humorous, sustained tour de force, never more than three or four pages.

PM: You read a lot of science fiction, and have expressed admiration for The Star Virus by Barrington Bayley and Three to Conquer by Eric Frank Russell. Any other science fiction books that you have particularly liked?

WB: Fury, by Henry Kuttner. I don't know, there are so many of them. There's something by Poul Anderson, I forget what it was called, Twilight World. There are a lot of science fiction books that I have read, but I have forgotten the names of the writers. Dune I like quite well.

PM: There is no particular science-fiction author that has notably influenced you?

WB: No, various books from here and there. Now, H. G. Wells, yes, The Time Machine, and I think he has written some very good science fiction.

PM: What about the other Burroughs, Edgar Rice?

WB: Well, no. That's for children.

PM: In The Ticket That Exploded you write: "There is no real thing-- all show business." Have Buddhism, Zen, and Oriental thinking in general exerted a strong influence on you?

WB: No. I am really not very well acquainted with the literature, still less with the practice of yoga and Zen. But on one point I am fully in agreement, that is, all is illusion.

PM: Has the use of apomorphine made any progress that you know of since you started recommending and advocating its use?

WB: No, on the contrary. Too bad, because it is effective.

PM: In a recent interview, you said that apomorphine combined with Lomotil and acupuncture was the remedy for withdrawal. What was wrong or insufficient with apomorphine to require the combination of two other elements?

WB: I found out about Lomotil in America some time ago, and then doctors have been using it here with pretty good results. The thing about apomorphine is that it requires pretty constant attendance. In other words, you've got to really have a day and a night nurse, and those injections have to be given every four hours. And it isn't everybody that's in a position to do that. But at least for the first four days, it requires rather intensive care. And it is quite unpleasant.

PM: And it's emetic...

WB: Well, no, there's no necessity; see, it's not an aversion therapy and there's no necessity for the person to be sick more than once or twice when they find the threshold dose. They find the maximum dose that can be administered without vomiting, and they stick with that dose. You'll get decreased tolerance; sometimes the threshold dose will go down. Usually, almost anyone will vomit on a tenth of a grain. So then they start reducing it, but as the treatment goes on, you may find that a twentieth of a grain or even less than a twentieth of a grain produces vomiting again. You may get decreased tolerance in the course of the treatment. So it's something that has to be done very precisely, and of course people must know exactly what they're doing. It's very elastic, because some people will take large doses without vomiting, and some people will vomit on very small doses. Continual adjustments have to be made.

PM: And acupuncture?

WB: Well, I thought immediately when I saw these accounts, as well as a television presentation of operations with acupuncture, that anything that relieves intense pain will necessarily relieve withdrawal symptoms. Then they started using it for withdrawal symptoms, apparently with very good results, and are using it here, I think.

PM: Most of your books definitely have a cinematographic touch. The Last Words of Dutch Schultz actually is a film script, and The Wild Boys and Exterminator! are full of cinematographic details and indications

WB: That's true, yes.

PM: Why haven't we seen any film made from one of your books?

WB: Well, we've tried to get financing on the Dutch Schultz script, but so far it hasn't developed. Very, very hard to get people to put up money for a film.

PM: What films have you liked recently?

WB: I like them when I go, when I see them, but it's rather hard to get myself out to see a film. I haven't seen many films lately. I saw A Clockwork Orange; I thought it was competent and fun, well done, though I don't think I could bear to see it again.

PM: Do you write every day?

WB: I used to. I haven't been doing anything lately because I gave a course in New York, and that took up all my time; then I was moving into a new flat there, so that during the last five months, I haven't really been doing much writing.

PM: When you write, how long is it each day?

WB: Well, I used to write... it depends ... up to three, four hours, sometimes more, depending on how it's going.

PM: What is the proportion of cut-up in your recent books, The Wild Boys and Exterminator!?

WB: Small. Small. Not more than five percent, if that.

PM: Parts of Exterminator! look like poems. How do you react to the words poem, poetry, poet?

WB: Well, as soon as you get away from actual poetic forms, rhyme, meter, etc., there is no line between prose and poetry. From my way of thinking, many poets are simply lazy prose writers. I can take a page of descriptive prose and break it into lines, as I've done in Exterminator!, and then you've got a poem. Call it a poem.

PM: Memory and remembrances of your youth tend to have a larger and larger place in your recent books.

WB: Yes, yes. True.

PM: How do you explain it?

WB: Well, after all, youthful memories I think are one of the main literary sources. And while in Junky, and to a lesser extent in Naked Lunch, I was dealing with more or less recent experiences, I've been going back more and more to experiences of childhood and adolescence.

PM: Parts of Exterminator! sound like The Wild Boys continued. We find again Audrey Carson, and other things. Did you conceive it that way, as a continuation of Wild Boys, or is it just a matter of recurrent themes?

WB: Any book that I write, there will be probably...say if I have a book of approximately two hundred pages...you can assume that there were six hundred. So, there's always an overflow into the next book. In other words, my selection of materials is often rather arbitrary. Sometimes things that should have gone in, didn't go in, and sometimes what was selected for publication is not as good as what was left out. In a sense, it's all one book. All my books are all one book. So that was overflow; some of it was overflow material from The Wild Boys, what didn't go into The Wild Boys for one reason or another. There are sections of course in The Wild Boys that should have gone into Exterminator!, like the first section, which doesn't belong with the rest of the book at all; it would have been much better in Exterminator!, the Tio Mate section. There's no relation really between that and the rest of the book.

PM: There was the Egyptian Book of the Dead, and the Tibetan Book of the Dead, and then The Wild Boys, subtitled "A Book of the Dead." Am I stupid in seeing a connection between them.

WB: Oh no, the connection I think is very clear: everyone in the book is dead. Remember that Audrey is killed in the beginning of the book, in an auto accident.

PM: Did you inspire yourself from the old books of the Dead?

WB: To some extent, yes. I've read them both; not all of the Egyptian one, my God, or all of the Tibetan one, but I looked through them. In other words, the same concepts are there between birth and death, or between death and birth.

PM: You have kept an unchanged point of view about the origins of humanity's troubles. In The Naked Lunch you wrote: "The Evil is waiting out there, in the land. Larval entities waiting for a live one," and in Exterminator!, "The white settlers contracted a virus," and this virus is the word. But who put the word there in the first place?

WB: Well, the whole white race, which has proved to be a perfect curse on the planet, have been largely conditioned by their cave experience, by their living in caves. And they may actually have contracted some form of virus there, which has made them what they've been, a real menace to life on the planet.

PM: So the Evil always comes from outside, from without?

WB: I don't think there's any distinction, within/without. A virus comes from the outside, but it can't harm anyone until it gets inside. It is extraneous in or??ìp

PM: Speaking of coming in and out, as you were arriving in London for a visit late in 1964, you were allowed only fourteen days by the authorities, without explanations. Have you had to suffer from a lot of harassment from authorities?

WB: Very little. That was straightened out by the Arts Council and was of course prompted by the American Narcotics Department. Allen Ginsberg had the same difficulties. The American Narcotics Department would pass the word along to other authorities. Well, I got that immediately straightened out through the Arts Council; I've never had any trouble since.

PM: May I ask the reasons for why you are moving to New York?

WB: Well, I like it better. New York is very much more lively than London, and actually cheaper now. I find it a much more satisfactory place to live. New York has changed; New York is better than it was; London is worse than it was.

PM: You have always described the System as matriarchal. Do you still have the same opinion?

WB: Well, the situation has changed radically, say from what it was in the 1920s when I was a child; you could describe that as a pretty hard-core matriarchal society. Now, the picture is much more complicated with the pill and the sexual revolution and Women's Lib, which allegedly is undermining the matriarchal system. That is, at least that's what they say they're doing, that they want women to be treated like everyone else and not have special prerogatives simply because they're women. So, I don't know exactly how you would describe the situation now. It's certainly not a patriarchal society--I am speaking of America now--but I don't think you could describe it as an archetypal or uniform matriarchal society either, except for the southern part of the United States. You see, the southern part of the United States was always the stronghold of matriarchy, the concept of the "Southern belle" and the Southern woman. And that is still in existence, but it's on the way out, undoubtedly.

PM: You call for a mutation as the only way out of the present mess. Right now, what positive signs, factors, or forces do you see working toward such a mutation?

WB: Well, there are all sorts of factors. Actually, if you read a book like The Biologic Time Bomb by Taylor, you'll see that such mutations are well within the range of modern biology, that these things can be done, right now. We don't have to wait three hundred years. But what he points out is that the discoveries of modern biology could not be absorbed by our creaky social systems. Even such a simple thing as prolonging life: whose life is going to be prolonged? Who is to decide whether certain people's lives are going to be prolonged and certain other people's are not? Certainly politicians are not competent to make these decisions.

PM: You hate politicians, right?

WB: No, I don't hate politicians at all, I'm not interested in politicians. I find the type of mind, the completely extraverted, image-oriented, power-oriented thinking of the politicians dull. In other words, I'm bored by politicians; I don't hate them. It's just not a type of person that interests me.

PM: What are your methods of writing at present?

WB: Methods? I don't know. I just sit down and write! I write in short sections; in other words, I write a section, maybe of narrative, and then I reach into that, but if it doesn't continue, I'll write something else, and then try to piece them together. The Wild Boys was written over a period of time; some of it was written in Marrakech, some of it was written in Tangiers, and a good deal was written in London. I always write on the typewriter, never in longhand.

PM: What is, in The Wild Boys, the meaning of sentences like "A pyramid coming in...two...three..four pyramids coming in..."?

WB: That is an exercise of visualizing geometric figures which I have run across in various psychic writings.

PM: Would you be interested in testing psychotronic generators too?

WB: Yes, the various devices described in Psychic Discoveries Behind the Iron Curtain. They have now come out with another book called A Handbook of PSI Discoveries, which is a how-to book telling just how to do Kirlian photography how to build all these machines and generators and so on. I'm very interested in experimenting with those if I have the opportunity, time, and money.

PM: In the mid-seventies, you write that you wanted to create a new myth for the Space Age. Is it what you are still trying to do, and do you use the word myth in a particular sense?

WB: I feel that I am still working along the line of a myth for the Space Age and that all my books are essentially one book. I use myth in the conventional meaning.

December 20, 2004

Marquis de Sade: nature rules, okay

I have to admit being suprised that the Marquis de Sade worked within, and accepted, the mechanistic French materialist precursors to physicalism.

I have to admit being suprised that the Marquis de Sade worked within, and accepted, the mechanistic French materialist precursors to physicalism.

So how you go from a deterministic world of physical particles in motion to the passions ruling the body, perversions, violence, and the subjugation and humiliation of women of de Sade's philosophy in the bedroom?

There is no morality in the mechanistic world, and no freedom, as human beings cannot act otherwise to their nature. Or the body unfree and freedom is the imagination?

Are we not ruled by the dark forces of nature? Or is it a case of being ruled by our desires? It is our desires that lead to sexual violence and mutilation. Is it a case of getting back to Nature giving free rein to sexual violence and lust?

Is that not a Christian way of understanding sexual desire, violence and human nature? On this account, the free reign of lust means without any moral inhibitions.That means exalting evil as virtue.

Presumably de Sade would have to hold that we are governed by our nature (and Nature). As there is little we can do about it, therefore we should simply enjoy life to the full, whatever his intrinsic nature dictates, as to do otherwise is to deny our nature. We can only exhibit and enjoy to the full our natural desires when we are freed from all moral and social restraints. So Nature determines that I enjoy myself, no matter at whose expense.

Since moral conscience is a reflection of prejudices and codes inculcated by training and upbringing, then the conscience needs to be destroyed.Freedom, then, is the absence of external obstacles.

So those who deny their darker desires and natures and try to be moral and virtuous are the ones most likely to behave badly, while the people who are socially condemned as immoral because they give free expresion to their dark desires who often display true virtue. The former live their lives within a rigid moralism and behavioral codes and have a supercilious social pretense. These paragons of society -- the priests and moral straightners -- act behind the facade of their pious sanctity to perform the cruelest, most despicable acts, sexual and otherwise.

That is de Sade is it not? Justine, suffers for her virtue, while her sister Juliette profits through debauchery. Justine is punished for her virtues - chastity, piety, charity, compassion, prudence, the refusal to do evil, and the love of goodness and truth.

December 19, 2004

Heidegger: overcoming metaphysics

This review of Heidegger's Zollikon seminars is interesting for two reasons. First it clearly states what Heidegger was doing with his destruction or overcoming of the metaphysical tradition. It says:

"Here we see Heidegger insisting once again, as he did in Being and Time, on the necessity of distinguishing an ontological analysis of Dasein, i.e., an analysis of its manner of being (disclosedness, openness, the clearing), from an ontic analysis, e.g., a causal analysis or an analysis that supposes a subject confronting an object. He also revisits his account of the historical reasons why contemporary thinkers fail to appreciate this necessity. In this connection Heidegger calls attention to the continued influence of Kant, Descartes, and Aristotle, much as he projected that he would do in the unfinished second part of Being and Time. ...In the seminars he also rehearses at length his earlier analyses of time and his criticisms of a natural, scientistic attitude that takes for granted that, at bottom, ’being’ means the same thing, whether the subject matter is the travel of photons, the life of a cockroach, or human existence."

In the context of the Australian philosophical tradition, which has been largely shaped by Anglo-American philosophy shaped by J.C.C. Smart we can interpret the mode of scientistic naturalism as physicalism. The take up of continental philosophy in Australia can be read, in part, as a recoil from physicalism, its philosophy of mind and preoccupation with the ontological nature of mental states by those following the Australian materialist trail blazed by Jack Smart (scroll down).

Physicalism sucked, big time. To put it into Heideggerian terms we can talk in terms of a questioning of the Physicalist World Picture. Another pathway of recoil---from Whitehead to Heidegger to Merleau Ponty.

However, what is even more interesting in Daniel Dahlstrom's Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews of Heidegger's Zollikon Seminars is the issue of the body in being-in-the world.

I've always read Merleau Ponty as extracing a very good interpretation from the buried themes of Being and Time, and then a building on it to a conception of an embodied being-in-the-world. I've always found this to offer one of the most innovative ways of crawling out of the reductionist physicalist flybottle to a new and different space.

Heidegger appears to concur with this reading of Merleau Ponty's innovative creation of new philosophical concepts. Daniel Dahlstrom's review says:

"Probably the most important new topic discussed at length in the seminars is a particularly weak link in those earlier analyses and a theme that one might expect him to confront in this setting: the body. Taking his cues from difficulties surrounding talk of “psychosomatic” and “somapsychic” illnesses, Heidegger turns to the problem of the body (like Husserl, Leib in contrast to Körper), though he does so by way of reviewing the account of Dasein’s spatiality that he gave in Being and Time. Without mentioning Husserl’s or, more importantly, Merleau-Ponty’s comparable studies, Heidegger analyzes such themes as blushing, phantom limbs, attention, being in pain, grasping, sadness, and gesture, among others. The lack of reference to Merleau-Ponty seems particularly egregious, not only given his extensive treatment of these themes, but also given his insistence both on the motility of perception and on construing the body in terms of a Heideggerian notion of being-in-the-world, an insistence that in both cases is iterated by Heidegger in the seminars. Indeed, at one point – in what amounts to a paraphrase of Merleau-Ponty’s own formulation – Heidegger equates “being-in-the-world” with “bodily having a world.”

Heidegger goes on to say Sartre and Merleau-Ponty managed to get only “halfway” to an existential understanding of the body, thanks to Descartes’ persistent influence.He couild have been more generous to Merleau Ponty.

December 18, 2004

Heidegger & Aristotle

Tis a common relationship for those scholars have spent time working through the texts of the early Heidegger, but it is not a well known one. Many do not see Heidegger as having a practical philosophy, let alone one about the ethics of practical life.

It is explored by Stuart Elden (see Works in Progress) in a paper called, 'There must be some Architectonic: Heidegger and Aristotle on the Politics of Phronesis.' Eldens text is a very detailed reading that shows how closely Heidegger read the Greek texts, and the way he uncovered the sedimentation of the philosophical tradition (scholasticism) on these Aristotlean texts.

Gadamer, who was a participant in this destruction, says in his Philosophical Hermeneutics, (pp.201-2) that what was uncovered was phronesis as a form of practical ethical knowledge that is distinct from the theoretical knowledge of science. This is the habit of deliberating well and making non-ruled governed practical and political judgements in concrete situations. It is a form of ethical knowing based on experience.

Heidegger sides with Aristotle's critique of Plato's understanding of ethics and the good life, then deploys this Aristotlean critique against the neo-Kantian value philosophy in 20th century Germany.

December 17, 2004

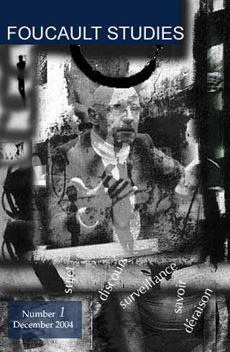

Foucault's toolbox

This is very good news. The first issue of Foucault Studies is now out.

It is a new electronic, refereed, international journal from Queensland, Australia.

It is a new electronic, refereed, international journal from Queensland, Australia.

The innovative cover design was by Maria Spanou.

It is good news because the journal is fully accessible online, and so it is an open resource. That is a radical break from the closed world of academic journals in which everything is locked up on a subscritption only basis. The digital shift is happening slowly in academia.

So it is good to see the journal operates in the ethos of Foucault rather than than the conservative academic elitism that locks knowledge away from the masses.

A Foucault quote:

"I would like my books to be a kind of tool-box which others can rummage through to find a tool which they can use however they wish in their own area... I would like [my work] to be useful to an educator, a warden, a magistrate, a conscientious objector. I don't write for an audience, I write for users, not readers."

That is how I use Foucault over at philosophy.com You pick what is useful for the job at hand.

Glancing through the articels I noticed this one by Neil Levy. The abstract reads:

"In his last two books and in the essays and interviews associated with them, Foucault develops a new mode of ethical thought he describes as an aesthetics of existence. I argue that this new ethics bears a striking resemblance to the virtue ethics that has become prominent in Anglo-American moral philosophy over the past three decades, in its classical sources, in its opposition to rule-based systems and its positive emphasis upon what Foucault called the care for the self. I suggest that seeing Foucault and virtue ethicists as engaged in a convergent project sheds light on a number of obscurities in Foucault's thought, and provides us with a historical narrative in which to situate his claims about the development of Western moral thought."

I pretty much concur with that, other than to add that his conception of care of self is a radical reworking of classical virtue ethics and the Stoic ethical tradition.

Nietzsche conference

This conference on Nietzsche looks interesting. It asks some good questions:

"Does Nietzsche, as some critics have argued, merely idealise time, transitoriness and difference in the same way that his predecessors idealised permanence, being and identity? What are the new conceptions of time that Nietzsche has to offer? What kind of historian was Nietzsche himself? What kinds of 'temporal' histories and 'historical' philosophies did Nietzsche write/or fail to write?"

A good chance to explore the eternal return chestnut.

As an aside the more I struggle with Klossowski on this the more I come to appreciate Joannes insights about text, subjectivity and reading. She says that

"...reading philosophical texts—and Nietzsche’s in particular—accomplishes a formative function in the subject’s life, specifically in terms of identity and desire. Acquiring the ability to ‘read’ and assess a philosophical text necessitates the incorporation of its structures and values. Reading requires a reorganisation of the self according to the imperatives of the text, to the extent that one becomes a product of the text one reads."

How true.

Maybe that is why I struggle with Klowwoski's text on Nietzsche. I resist becoming a product of this text.

December 15, 2004

Across the Australian grain

Given my interest in ethics, I thought that I'd throw this paragraph into the mix, stir it with a few comments, and finish with a question.

'Conventional wisdom either indicts poststructuralism and its forebears (Sade, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Bataille, Blanchot) on the grounds that they are devoid of ethical potential, or else it ignores them altogether. Reading and actually attempting to follow an astounding array of poststructuralists (a task all too many of those who declare themselves their enemies are loathe to undertake), Jay examines what he quickly allows is their "intense and abiding fascination with moral issues" which in turn demands that serious thought be given to the ethical questions they raise (39). Examining several ruminations on ethics contained in texts by Foucault, Lyotard, Emmanuel Lévinas (obliquely), Lacan, and others, Jay reiterates their common resistance to normative moral systems -- something he believes makes it nearly impossible for them to envision egalitarianism, mutuality, and reciprocity. Their ... ethics -- a sort of aesthetics of self -- opens upon somewhat stark sociological whimsy which nevertheless jibes paradoxically with recent Anglo-American moral meditations by Alasdair MacIntyre and Bernard Williams. Convinced as poststructuralists are that humanism led to the several coercive political systems of the twentieth century, they remain doggedly antihumanistic. But Jay's predilection for ideological dialogue and even accommodation of tenets belonging to the most inimical philosophies can be credited in his refusal to dismiss poststructuralist ethical skepticism most in evidence when collectivities are characterized as "unrepresentable" (Lyotard), "unworkable" (Nancy), "unavowable" (Blanchot). One can feel Jay pushing and pulling, trying to adapt these conceptualizations to Habermasian communicative discourse in order to prevent their stagnating as mere "evocative rhetoric"'.

The quote is from this review of Martin Jay's 1993 book, 'Force Fields: Between Intellectual History and Cultural Critique.' I have not read the Jay text, nor am I likely to, even though I respect Jay's commitment to engaging in debate with diverse cultural and philosophical traditions through critical practice.

What can we make of the paragraph? Analytic ethics has been very fairly impoverished given the postivist legacy of emotivism, the formalism of Kantian ethics and the technicalism of utilitarianism. Is the indictment, that poststructuralism and its forebears (Sade, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Bataille, Blanchot) is devoid of ethical potential, on target?

I reckon that (Anglo-American) conventional wisdom is quite wrong on the devoid of ethical potential. An ethical current runs through poststructuralism and its forebears. What we see here is the poverty of Anglo-American discourse, which has been habitually hostile to poststructuralism. That ethical current is deeper than ethical scepticsm towards humanism or convcentional moralities.

The aesthetics of self is a reference to Foucault but it is too narrow to capture the ethical concerns of Nietzsche about nihilism and the revaluation of values; or Heidegger's turn towards an ecological ethics of letting be in response to a technological mode of being. This implies a particular reception of Nietzsche that should be spelt out.

I've suggested that if we adopt the perspective of classical Stoic ethics, then we usefully read the ethical currents of poststructuralism and its forebears in terms of the a medical conception of philosophy that diagnoses our sickness, the disintegration of a moral community, the breakdown of moral language, the blighting of character or personality from a damaged life, and the need to revalue our values in a nihilistic world to live a more flourishing life.

What this ethical strand implies is a reevaluation of the modern (utilitarian) Australian Enlightenment, in which the liberal subject seamlessly enframes the world as an object of reflexive knowledge. Adorno's pessimistic vision of an increasingly instrumentalized modernity is well taken by this ethical strand in an Australian context. That strand then becomes environmental in orientation, as it interprets modernity as overstressing the tendency to commodify nature and, to degrade the earth as a source of life. This ethical strand would then go through and beyond Heidegger.

A question can be posed. Can those who who are hospitable to postmodern currents of thought nonetheless seek to recover something of value from the dark ruins of the once-heavenly city of Enlightenment discourse?

December 14, 2004

emotion and reason

I guess I should have read Bataille's Inner Experience before reading the latter On Nietzsche. But that's the way with bookshops in Australia is it not? They had one text --On Nietzsche--- but not Inner Experience. So I bought the former, ordered the latter, and discovered that Guilty is out of print. So I had little choice but to sit down and start reading On Nietzsche.

And I found that text dam near incomprehensible. Suprise suprise. By the time I had struggled through reading the first two parts, 'Mr Nietzsche' and 'Summit and Decline' I had concluded that this text was about religious feeling. I then mapped this in confessional terms and I understood that Bataille placed these intense, private emotional states in opposition to the public world of work.

I found the juxtaposition naive, given my background in Stoic philosophy of managing the passions ('serpents in the soul') in public life. Naive more than a

alien.

The passions in the Stoic tradition are understood as inclinations of thought, or judgement, and a part of reasoning rather than passion being placed in opposition to thinking; a therapeutic philosophy delves into our subjectivity in order to develop a rich sense of what we are experiencing in our way of life; and it works upon our strange fears and anxieties, our excessive loves and grief, and our crippling angers without dismissing them as irrational, as did Kant.

On this account our passions can be irrational in the sense that the beliefs they rest on may be false, or unjustified. They are not irrational in the sense of having nothing to do with reasoning or argument. The reason? There is a cognitive dimension to our emotions, and this has a close connection to our ethical judgements about what is important or ethically significant in our lives and what is not.

But Bataille, for all his talk about morality, was so religious. What interested him was religious ecstasy.The references to Nietzsche were very misleading. This religious focus is upfront in Inner Experience. He opens by saying:

"By inner experience I understand that which one usually calls mystical experience: the states of ecstasy, of rapture, at least mediated emotion. But I am thinking less of confessional experience, to which one has had to adhere to now, than of an experience laid bare, free of ties, even of origin, of any confession whatsover.This is why I don't like the word mystical."

Fair enough.

It would have been nice to have known that before I started reading On Nietzsche. Then I would have known that Bataille was reading Nietzsche in terms of Nietzsche's own "mystical" states, rather than the more classical themes of the disintegration of a moral community and moral language, the blighting of character or personality from a damaged life, and the need to revalue our values in a nihilistic world so as to live a flourishing life.

So what have I gained from the struggle with On Nietzsche so far? That Bataille is thinking about the emotions and possibly about the emotions as forms of evaluative judgement. Though I am not sure about the latter point of emotions as value judgements.

Public Apology

Gary, Jo, Ali, everyone else,

My most abject apologies. A web page is not the place for a drunken rave. It won't happen again. I know it is an obvious contradiction but I don't drink, at least, not usually, and I couldn't tell you the last time that I devoted a whole day to it. There's no excuse. Sorry again.

December 13, 2004

Bataille and Booze

Dearest Gary,

are you Trying to provoke me? Boredom is like beauty - it lies in the eyes of the beholder. Start your philosophical education again. Avoid all the things you read before. Try to get all that shit out of your head. This is radical surgery. It's your only hope. Anybody who thinks that Bataille is boring is brain-dead. Come on, mate, this is crap. I've bypassed all the Heidegger stuff in silence but this is crap. I'm not going to say the same old things over and over again. You don't understand and I don't give a fuck how many Americans like what you say, it's shit. If you can't understand Bataille you can't understand the C20. Forget about looking outward and looking inward. If it doesn't make sense do some more work.

Jo,

I've still got some time for you. Forget about the conscious and the unconscious. I don't know what you are doing for your PhD but I need to know. Tell me. Let's start a real conversation. Who's Ali? Habermas is a conservative nothing. I don't care how he relates to Heidegger. It's irrelevant. Read Adorno. If you can't understand it, read it again. This is no bullshit. Don't waste your time on crap, Ali.

Hey Jo, I'm coming to Melbourne at the end of next month and I want to see you. Who's your supervsor? Never trust an academic. I've looked at all your pictures and they're great. Are they your kiddies? Is that your old man? You are beautiful.

What has this to do with philosophy, you ask? The answer: everything.

I'll be on Nicholson Street. Let's get in touch.

Don't give up on Klossowski. Don't give up on Bataille. Don't give up on Adorno.

I don't usually drink but I'm pissed to the eyeballs. But hey, don't give up on me, Jo. It's nearly Christmas, it's been a bastard of a year, and I'd love to talk to you. How about it? Let's meet at the end of next month.

December 12, 2004

Bataille: On Nietzsche#22

Lets face it. Bataille is boring. Dead boring. Boring because he is such an individualist.

For a far more sympathetic and insightful reading of Bataille, see Joe's earlier post here.

Boring is my reaction, even though I try to get in the mood by reading him late at night in the bowls of the Canberra political machine at the end of a long day, with Sky News on endless repeat. Is there any other way to read Bataille?

Believe me, though Canberra is a world of mesmerizing surfaces, seductively addictive but depthless, it is also a very existential experience full of fear, despair, terror and death. The machineryof power and spectacle can crush you, and many have been. There are bodies everywhere. People hug the walls avoiding your eyes, pretending your bodily existence is nothing, as they walk past you in the corridors. Once they were your friends. Now they are hurt, wounded and full of shame. People become shadows of their former self due to losing an election. All that energy fighting is wasted. They feel wasted, tired, exhausted and depleted. Life has no meaning anymore.

On Nietzsche is all about Bataille alone and preoccupied with his inner experience. There is little conception of ethics involving self and other, or of belonging to a public world. With Bataille we are locked up in the world of Cartesian individualism, trapped in our subjectivity, romancing the passions, resisting normative moral systems and preoccupied with the relentless and useless emptying out of energy.

On Nietzsche is little more than a diary of an isolated individual dealing with his pain. One can be alone writing but in Canberra one knows that one is still a part of the machinery of political power, and that this power often works to easily extinquish you. However, Bataille fantasies that he is actually alone in the world, alone in the cosmos. It's mythmaking.

In Ch 13 of the 'Summit and Decline' section (part two) Bataille says:

"Making my inner experience a project:doesn't that result in a remoteness, on my part, from the summit that might have been?"

And that is what it is about. A wounded Bataille lives. He explores his subjectivity and his excessive desires. He has a moral goal that is beyond him but follows the slopes of decline into exhaustion.

Ho hum. It reads like a Catholic confession without the priest.

In chapter 14 Bataille puts aside his desires for autonomy and his longings for freedom from a public powers (good old negative freedom) for more of a human autonomy at the heart of a hostile silent nature. He is alone with his terrors gripped by feelings of desperation and living at the limits.

So are those who inhabit the political world in Canberra. They are alone with the rollercoaster of emotion even though they are still part of the workings of political machine. So I can connect to Bataille's subjective processes of excess that threaten to overwhelm my ego and identity. I experience the terrors and feelings of desperation daily.

The terrors, being gripped by feelings of desperation and living at the limits are part of the every day political experience: the destructive chaotic impluses that threaten to overwhelm you are something that you just have to live with. You are living with death and wondering, is there life after politics?

So what does Bataille actually say before we turn to the diary proper?

This what he says-- and I'm going to give the space to say his bit since this text is not online:

"...while I can't get along without acting or questioning, on the other hand I am able to live---to act or question---without knowing. Perhaps the desire to know has just one meaning---as a motivation for the desire to question. Naturally, knowing is necessary for human autonomy procured through action by which the world is transformed. But beyond any conditions for doing or making, knowledge finally appears as a deception in relation to the questioning that impels it. When questioning fails, we laugh. Ecstatic raptures and ardors of love are so many questions---to which nature and our nature are subjected. If I had the ability to respond to moral questions like the ones I've indicated, to be honest, I'd be putting the summit at a distance from myself. By leaving open such questions in me like a wound, I keep my chance, I keep luck, and I maintain a possible access to these questions."

'Knowledge appears as deception in relation to the questioning that impels it'?

What kind of bullshit is that.

You only survive in the political machine through embodied political knowledge. That allows you to read the political power plays that can wipe you out. Many cannot read the body language as they---wearing the mask of the lobbyists wander through the building, going from appointment to appointment to persuading this person or that. The invisible play of power is circulating all around them but they never really see it. They are too caught up with up their own concerns. Though their (theoretical) knowledge of how Canberra works is deceptive, the tacit embodied knowledge of the play of power is what keeps you alive.

That kind of thinking works from the pre-choate and the quizzical gap; from the nagging tension and the razor sharpness of contradictary forces. The knowledge from this embodied thinking often takes place within empty places, and the voids that suddenly appear between the powerful conceptual schemes at work in the knowledge/power machinery. This kind of knowledge arises from the breakdown in the relationships between the individual concepts when things go bellyup.

So we live in a postmodern political world of fractured bundles of concepts (eg., ladder of opportunity) which become isolated in their shining splendour (eg., Medicare Gold) like so many galactic systems, and which drift apart (aspirational suburbanites) in the empty space of the political world.

Bataille writes: 'When questioning fails, we laugh.'

The questioning is a survival tool to negotiate the political sea full of icebergs. Questioning involves deciphering the appearances of the play of poweras refrated in the glittering surfaces of the media. It is not a question of the questioning failing, and then breaking out in laughter. The questioning and deciphering continue, as it is a part of living in a political life. Turn the questioning off and you die. And the laughter? That is thrown at you by the mocking victors, whilst the losers laugh their bitter death.

And the ecstatic raptures? That excess comes from victory, just as the terror comes from defeat. These, and the awful laughter, are built into the political life. It does not implode it.

As you can see I am not much impressed with G. Bataille, who wears the romantic mask of the artist/writer in On Nietzsche. He does not understand that the destructive process of the summit and decline (the informe?) which confuses the world of meaning and form with its clear-cut differences is the core of the political machine. It is how the political machine works.

So you can see why I find Bataille boring. It is all too close to the confessional.

December 11, 2004

Heidegger: forgetting Hegel

In his article Heidegger's Challenge and the Future of Critical Theory Nikolas Kompridis highlights how Heidegger turned away from the Hegelian moment in his ethics. As we have seen that moment understood freedom for self-determination (authenticity in Heidegger's vocabulary) to be both dependent upon, and facilitated, by our relationships with others.

Nikolas says:

"Unfortunately, Heidegger stranded this important insight in the first division of Being and Time and thereby undermined the development of his conception of authenticity in terms of the notion of resoluteness. When Heidegger lays out the meaning of resoluteness in the second division, it appears to belong to a dialogical structure of "call" and "response." Yet the relationship between "the one who calls"and "the one to whom the appeal is made" is not developed on the model of the relationship between self and other, but exclusively on the model of one's relationship to oneself. Heidegger clarifies the meaning of resoluteness as an openness or receptivity to the "call of conscience" independently of our obligations to others. The call of conscience is the call of care, and it comes from Dasein itself. Heidegger deliberately formalizes the existential-ontological meaning of this "call" so that all obligations "which are related to our concernful being with others will drop out" (BT 328/283). The whole construction of resoluteness suffers from this regressive step: each individual Dasein must get into the proper relation to itself before it can clear the way for others, before it can become the "conscience" of others. Consequently, Heidegger cannot win back that ethical dimension of self/other relations constitutive of freedom as self-determination."

Very insightful. I've gained more from this passsage and the one in the previous post, than my struggles with Joanna Hodge's Heidegger and Ethics, which I picked up in a second hand bookshop in Melbourne a couple of weeks ago.

Resoluteness means holding onto anxiety (the breakdown of the world) rather than fleeing it, and then getting back to the public world. Resoluteness needs to be understood in terms of Heidegger's anti-mentalist, anti-subjectivist conception of human existence and practice. Human understanding and practice are essentially situational and context-dependent. (The latter Heidegger replaces "resoluteness" with the idea of releasement or Gelassenheit.)

December 10, 2004

Heidegger: A Hegelian moment

In his article Heidegger's Challenge and the Future of Critical Theory Nikolas Kompridis makes a very interesting observation about Heidegger's ethics in relation to Hegel. Referring to a couple of passages in Being and Time (BT 158-159/122,) he says:

"This passage, with its resonances of the dialectic of slavery and domination from Hegel's Phenomenology, represents one of those altogether rare occasions where Heidegger actually contributes insightfully to enlarging our understanding of how our freedom for self-determination -- authenticity, in Heidegger's vocabulary -- is both dependent upon and facilitated by others. Our relation to others can be based on (implicit or explicit) domination or it can be based on a cooperative realization of authentic freedom. Heidegger -- at least in such passages as this -- understands correctly that freedom that is not simply negative freedom requires more than respect for the autonomy of persons, and more than mere recognition of the other's claim to self-determination; it requires the recognition that the realization of the other's freedom is as much my responsibility as hers."

This is what a would call a Hegelian moment. It interprets authenticity as self-determining freedom that involves the freedom of others.

Nicolas then highlights the significance of Hegelian moment. He says:

"For once in Being and Time, the other is not simply an ontologically ineliminable feature of intersubjective structures of intelligibility, of a world which becomes accessible in the first place only in so far as it is a shared world; rather, the other is she through whom I learn to realize my freedom, and to whom I am accountable. I can clear the way for the realization of the other's freedom or I can get in the way; we can learn from each other or we can fail to learn -- in which case we will fail to realize our freedom. But we can only learn from each other when we recognize the ineliminable role of intersubjective accountability and recognition in the constitution of authentic, self-determining freedom."

This is insightful because Heidegger's understanding of authenticity is often interpreted in relation to Kierkegaard not Hegel.

Kierkegaard gives a very individualist account as a reaction to his understanding of Hegel: he read Hegel as overemphasising world spirit at the expense of the individual and the world of their own. Heidegger recoils from the overemphasis on individual subjectivity and recovers a shared public world.

December 09, 2004

Klossowski and Psychoanalysis?; Plug for my radio archive

Hi Gary and Trevor,

I've been occasionally checking the blog, but am very busy at the moment trying to finish off a chapter... there have been a number of things coming up in discussion, though, to which I know I should respond (need to respond), for the benefit of my own research. It's funny that Klossowski keeps coming up because I'm trying to keep away from all that at the moment and concentrate on other things (was it me it began the discussion on Klossowski, or Gary? Perhaps I'm experiencing a return of the repressed here). Anyway, I digress...

It is highly likely that I am over-estimating the influence of psychoanalysis on Klossowski's work. What Trevor said the other day about Klossowski's concern being "to overcome individuality" through the eternal return is perfectly correct. I suppose that what interests me is the relation that Klossowski draws between the eternal return, the dissolution of identity, and what he calls Nietzsche's "valetudinary states." His argument is not that Nietzsche's sickness (acute bouts of migraine, dispepsia, vomitting) gave rise to his philosophy, but rather that a certain attitude toward his sickness—i.e. taking his sick body as an object of study—gave rise to a particular perspective on the formation of the individual, and perhaps a program within Nietzsche's philosophy of destabilizing such individuality.